by College Goals

With college admission decisions made and released, the attention of students and admission officers turns to the tricky challenge of the waitlist. And rarely has the process seemed more chaotic than this year, in which many selective colleges faced higher application numbers, lower admit rates, and greater uncertainty about their yield.

There are many reasons why colleges run waitlists. A waitlist decision acknowledges the good work of strong applicants for whom there wasn’t space in the class. It also helps placate alumni, donors, and faculty whose children were not admitted.

Above all, a waitlist helps a college manage its enrolment numbers. Colleges cannot afford to have empty seats in their first-year class because too many admitted students opted for another offer. But nor do they want double dorm rooms turned into triples because more students than expected accepted their offer. So, they take their best-informed shot – and it is a remarkably good one! – at estimating how many students to admit in excess of the actual number they want in their class.

Even as they decide whom to admit and to deny, though, admission offices also build additional flex into the system by waitlisting many strong applicants. They can, then, in the months after admission decisions are released, continue to add more students to the class if the yield is lower than anticipated. This buffer is especially important in a year such as 2022, when the usual calculations about yield have been blown up by the uncertainty sparked by test-optional admission. By using a waitlist to protect yield, colleges can also pick the candidates that will help them fill gaps in their list of institutional needs – more women mathematicians, oboists, chemical engineers, underrepresented students, first-generation applicants, and so on.

Being waitlisted leaves students in a tough spot. They are happy to remain on the admission radar, but also realize that coming off the waitlist can be a very long shot. In 2020, for example, Chapman in Southern California admitted well over half the students they waitlisted. More typical, however, is the experience at CalTech, which admitted only 10 of the over 300 kids to whom they made a waitlist offer. Or Michigan, which admitted 1,248 students after waitlisting 20,723.

Faced with such odds, what is a waitlisted student to do? The short answer is to continue pursuing the college while also committing to another:

- Make sure you know the deadline for committing to the waitlist, and don’t miss it.

- Note all instructions in the waitlist letter. Does the college encourage you to write an email, submit a note to the admission portal, or tell you unambiguously that they don’t want to hear from you?

- If there are no instructions or if you are encouraged to submit a note, address and email it to the regional admission officer if you know who that is. The more personal your letter, the better! If you don’t have a name, address and email the letter to the Dean of Admission or, as a last resort, to Dear Admission Office at the general undergraduate admission address.

- Be respectful of admission officers’ time constraints and keep the note reasonably short and concise.

- On your way to stating your continued interest, it is okay to express some disappointment, but not frustration or resentment. Better to keep the tone clear, good-humored and optimistic. Being either obsequious or demanding will only alienate the reader.

- Add reference to whatever drew you to the college in the first place – perhaps a particular major, research opportunity or such – to help remind the reader of your thoughtfulness in choosing that school and explain your continued interest.

- If there are any updates to add – an award, an important project completed, or something of which you are particularly proud – tell the reader about it.

- Normally colleges are reluctant to waitlist students who were already deferred from early admission. But, this year, many students find themselves in that position; if this is true for you, feel free to remind the college that your interest has not waned since you first applied.

- Don’t refer to the decisions of other colleges, however. It will play no role in a college’s decision.

Colleges will make waitlist decisions based on their own needs and will likely do so in waves rather than at one set moment. Therefore, the coming months will require resilience and optimism on your part, but also common sense and honesty. You need to visit colleges that have already made you an offer, accept one of those offers (from which you can withdraw if you come off a waitlist), and along the way allow yourself the excitement and joy of this moment. Whatever experience you seek at college, achieving it will depend on the choices you make once on campus, regardless of where that is.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

by College Goals

In preparing their applications to college, high school students are encouraged to be authentic, engaged, passionate, and committed. These are indeed great aspirations, and, hopefully, kids get the message that being true and honest with themselves and putting together a good college application should not be at odds with each other.

One quality usually missing from this list of exhortations, though, might be the most important one: be empathetic. Empathy is a powerful idea whose definition often depends on context. For some, empathy is the same as sympathy, the state of caring for others and “feeling their pain.” It is an emotional response to a shared humanity. “I work in a food pantry for the poor because I feel bad for those who feel hunger; I teach kids how to play basketball because I know how much joy I get from it.” We believe such compassion to be a powerful part of children’s sociality and work to cultivate it. And when colleges ask applicants to write about how they help make the world a better place, it is this kind of empathy that students lay claim to and that admission officers wade through.

In urging students to feel sympathy for those with less privilege than they have, though, we might want to encourage them to do more than feel another’s pain. We also want to suggest a shift in perspective in which they go beyond describing their response towards imagining and interrogating how the other side in this equation feels. Social psychologists call this “perspective taking,” and define it as “the ability to understand how a situation appears to another person and how that person is reacting cognitively and emotionally to the situation.”

Why does this matter to how students present themselves in their college applications? In reading about or listening to how students describe their community service, I am always struck by how they see it as a one-way street: they feel bad for someone who might not have what they do and tell us what they have done to alleviate that need. They rarely seem to realize that there is also another side in this philanthropic equation. The result is variations on the so-called “poor but happy villagers” community service experience that has become so frustrating – and even toxic – to admission officers. They read countless essays about suburban kids teaching, contributing to, and “giving voice” to those who are less privileged. These essays are filled with good intentions but lack even a rudimentary understanding of the inequality and lack of reciprocity in such philanthropic exchanges: the less privileged are merely there to be acted on, to be helped and, hopefully, to be grateful for the assistance.

Don’t misunderstand me. I think such service work can be hugely enriching to a student and can reflect a well-honed sense of social obligation, which I applaud. But we might want to open a conversation with young adults – as parents and as counselors – about what and who is on the other side of that helping hand; to add to their emotional sympathy for the less privileged some of the awareness that comes from a more rational empathy.

Shifting perspective and seeing an exchange from the viewpoint of another, also offers students useful insights about other parts of the application process and, indeed, of life. When students present themselves in essays and interviews, it is often clear that they have not given much thought to who their audience is. It is a one-way conversation: they ascribe to themselves the qualities they feel colleges value (I am determined, helpful, diligent, resilient, keen to help others). It does not occur to them that what they’re trying to say may not be what the other side is hearing! They reference extensive foreign travel, for example, sure that the admission reader will appreciate their global citizenship, when, in fact, the reader hears a blithe catalog of great privilege. And when they describe tutoring an underprivileged fellow student, they rarely consider that admission officers might have been such low-income students themselves — and could find their tone patronizing.

As educational counselors we work in the hope that whatever kids learn from applying to college – about choices and consequences, about good writing – they will bring to bear on other parts of their young lives too. In this, there are few skills more valuable to them than moving from seeing the world strictly through their own eyes, to understanding that in their every interaction with another, there is another viewpoint present too.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

by College Goals

Students who attend boarding school get to live, learn, and thrive with motivated peers from around the world, supported by compassionate and dedicated faculty who serve as teachers, coaches, and dorm parents. At boarding school, students wake up each morning in a community buzzing with energy and know they are part of something special and unique.

LIVE

Life at boarding school is exciting and full of possibilities. Boarding school students report spending more time engaging with their communities and exploring their passions than students at private day schools and public schools[1]. Since students live and work alongside each other and the faculty every day, from the stage to the studio to the field, students have nearly endless options for immersing themselves in their interests and discovering new ones.

Along the way, students form meaningful relationships with caring educators who offer inspiration, guidance, and motivation. Coaches, teachers, and dorm parents are committed to creating supportive, nurturing environments where students feel inspired to grow as learners, members of the community, and leaders. In fact, 77% of boarding school students say that boarding school gives them the opportunity to lead[2].

LEARN

Going to class at boarding school is inspiring. Not only do students learn from high-quality teachers, but students also report being surrounded by motivated peers, making the learning environment rich and rewarding. Students’ classmates are also their teammates, bandmates, and roommates — so the learning doesn’t stop at the classroom door. Exciting and engaging conversations happen in dorm common rooms, fueled by snacks made by dorm parents.

Students feel academically challenged at boarding school. Small class size and easy access to faculty outside of the academic day allow students individualized attention so that they can also feel supported on their rigorous academic journeys. Teachers meet with students one-on-one to review everything from math concepts to essay writing techniques. At boarding school, students are both challenged and supported and feel intellectually inspired and academically satisfied.

THRIVE

Ready to face the challenges of college and beyond, boarding school students are prepared to thrive in the world after high school. Living on campus, learning with motivated peers, and engaging in leadership opportunities are just a few of the ways that boarding school sets students up for success. A majority of boarding school students report feeling prepared to succeed in college.

When asked if they would go to boarding school all over again, 90% of graduates said yes! At boarding school, students develop self-motivation, independence, and the ability to think critically and creatively. These skills not only help with college readiness, but they also set the foundation for career success later in life. Boarding school — and all that it has to offer — is an experience that lasts for a lifetime.

[1] Begin the Adventure of Your Life, © Copyright 2009-2019 The Association of Boarding Schools

[2] Begin the Adventure of Your Life, © Copyright 2009-2019 The Association of Boarding Schools[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

by College Goals

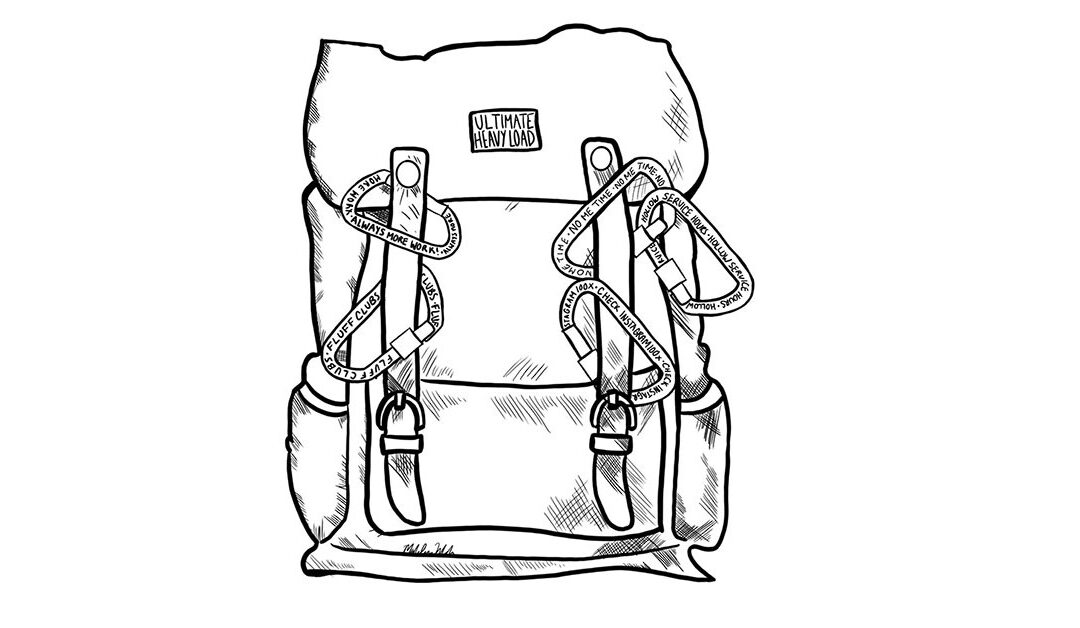

While I was walking through the snow (yes … we still get snow in March in Rhode Island) with one of my best friends a few weeks ago, she began telling me about a coaching framework she’s been working on—centered around a backpack. My friend Brountas (I call her by her last name … something that stuck during our college years together) owns an executive coaching business (https://www.linkedin.com/in/jen-brountas-16b731/). She uses the backpack analogy as a way to help her clients prioritize the things occupying their headspace. A backpack is a useful tool, but it has a limited capacity and a tendency to collect stuff that weighs you down. I couldn’t help but think that her framework and analogy could benefit my students as they transition into a post-pandemic world.

Brountas described her backpack idea as a way to talk about what feels awful and what feels good in our lives, and the consequences of letting the best parts of ourselves get lost in the load. I think a lot of my students would agree that the weight of junior and senior year of high school can “feel awful and overwhelming ” just like the weight of a too-heavy backpack. Everything about these later years of high school feels important … there is so much pressure to have just as heavy a backpack as everyone else, especially when thinking ahead to college. In fact, students often tend to “clip on” more responsibilities, like carabiners that create more weight on their shoulders.

“Think about what you miss and don’t miss” is a phrase I’ve heard many times over the course of the last year. I think most of us can quickly rattle off a few things we’ve missed throughout the pandemic and others we would happily toss out of our bags. It’s fun taking the time to reflect, but it’s much harder to actually leave some of your old life behind—to physically remove the weight or change the way you engage with the items that gnaw at your side. This spring, don’t just think about what’s next; instead, take action and make the leap forward to make your high school years the best they can be. A “big” bag full of all the right “things” doesn’t need to be heavy.

Stop & Unpack:

What “Rona” (as my students like to call the virus) did was force you to stop. It forced you to put aside your heavy load for a while. As Brountas says, “Feel the release. Step away from the bag and be conscious of what’s going on so that you can have a fresh perspective.” Before you sling the heavy bag back on your shoulders, I encourage you to unpack each item and sift out the “trash.” Is sitting on the bench at your team’s games getting you down? Maybe let that go and pick up something that makes you feel lighter and better represents the person you’re becoming.

Sort:

Sort the commitments in your life into categories: activities, clubs, the classes you’ve signed up for, jobs, internships, projects, time for sleep, time with friends and family, etc. What means the most to you? What would you like to leave behind? This act of reprioritizing isn’t something you should be ashamed of, it’s something you’ll have to do for the rest of your life. You’re just setting new goals!

Repack:

What do you want to take with you from the pandemic? Did you learn new skills? Strengthen your work ethic and confidence? Include these intangibles with your other priorities and make sure you have enough space — the type of space you enjoyed in your life as your heavy commitments shut down this year.

Try It On:

How does it feel? Is it still heavy in one area? Uncomfortably rubbing your side? If so, be aware of the irritating item in there that might need some reshifting. Maybe you just need to look at it differently? Perhaps a slight adjustment, like taking on a different role, forming a study group, or asking friends to join you in an activity can help make it feel more comfortable in your bag.

As schools go back to in-person learning, let’s talk through your re-entry and what’s most important — so that you don’t tip over from too heavy a bag. I believe a strong college application is closely tied to the joy and personal growth that comes from making good choices, and as Brountas says, “Monitor your backpack’s framework: it should be powerful and effective but not overwhelming.” An ideal weight, without filling your bag to the brim, allows you to walk with confidence and more intentionality as you move through your days and put time into what matters most to you. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

by College Goals

A recent article by Verónica Leyva takes issue with students paying undue attention to their choice of majors when researching colleges. In Major Myths, Busted, she argues instead for approaching the college search with an open mind, agnostic about any one path towards a degree. There are, after all, countless pathways to many careers, and colleges tend to be more interested in students who are motivated to learn than those narrowly focused on a major.

I think that Ms. Leyva’s arguments are absolutely sound and we should encourage high school students to identify their academic interest – a desire to engage with certain ideas or questions or modes of learning – and not simply a prospective major – an academic basket of courses set by faculty in the field to enable students to reach towards mastery in one discipline.

To the reasons why high school students should not fixate only on their prospective major, I would add the fact that they will likely change their minds anyway! Little point to researching only colleges with outstanding programs in Astrophysics if in the end you might opt to major in Anthropology instead! (I remember fondly a freshman advisee of mine at Brown who came set on studying Physics, before cycling through Philosophy and graduating as a Music major!) As Homer Simpson reminded Lisa, there is a time and a place for everything and it is called college – a time to try new ideas well beyond the narrow prescriptions of high school and challenge your mind beyond your own expectations. And most high school students are so trained to the narrow “boxes” of five core academic disciplines that they have little concept of how those translate into the 100 or more majors of a typical liberal arts university anyway!

There are good reasons for our current pushback against the tyranny of the major in students’ perception of where they should go to college and why. Many counselors have sat with students who, in months past, had lit up as they talked about their passion for the study of history or for the exploration of their favorite solar system. But then college admission comes into play, and suddenly they fixate on applying for the hot major du jour – computer science, chemical engineering, data science. This in spite of the work of economists like Doug Weber, who has shown that while right out of college STEM fields might yield more professional success, they do not inevitably pay better when measured by lifetime earnings.

And yet, having said all this, after twenty years as a college and academic advisor, I have also come to doubt how far we should go in the opposite direction, towards encouraging high school students to ditch all consideration of prospective majors. In part, this is because of the admission process itself (as I noted in a recent post). Majors are the bureaucratic building blocks of an undergraduate degree. Even the majority of liberal arts colleges that allow students to defer declaring a major for a year or two, still ask about intended majors in their applications. A college where the Environmental Studies department has just expanded might well want to make sure that those professors have a gratifyingly large number of prospective majors; and a college where the Classics faculty takes an interest in admission, might well take note of exceptional young Latin scholars.

Moreover, having students think about prospective majors is not at odds with having them identify exciting intellectual reasons for going to college. In fact, seeing how their intellectual interests connect with a particular academic discipline can help give teenagers a scaffolding with which to explore the things they find curious and exciting. I remember, when I first went to university eons ago, how validating it was to realize that people who were experts in the things I was curious about had thought those mattered enough to gather a corpus of knowledge about them and call it a History major! The practitioners of an academic discipline also use their own linguistic conventions to express their questions and concerns – and how liberating for young people to gain insight into that language in order to express their own ideas!

Ultimately though, my point is simply that an American liberal arts education is an extraordinary way of thinking about one’s learning, and students should look at the exciting range of possibilities it offers them, rather than cast around for a narrow academic box to climb into. But college is also not summer camp, and a conversation about majors might be another way to encourage high school students to view their learning with an equally important and exciting search for rigor and intellectual depth.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]