Reflection on Legacy Admission

As our juniors begin to build their application plan and timeline for next fall, we want to update you about the rapidly changing role of legacy admissions.

As you may know, many colleges and universities have historically given some preference in the admission process to the children of alumni. Studies have found that at some schools, legacy candidates were more than four times as likely to be admitted as non-legacy candidates with similar academic credentials. As recently as 2021, the Harvard Crimson reported that more than 30% of their current students were related to Harvard alumni, and, at Stanford and Cornell, the number is closer to 15%. Indeed, the practice has been most common amongst highly selective institutions, those defined as admitting fewer than 25% of applicants. These colleges have been motivated to admit legacy students at higher rates because they tend to come from wealthier families who may be able to give generously to their alma mater.

But that tide seems to be changing.

As early as 2014, Johns Hopkins University did away with its legacy preference, and, not long after, Pomona, Amherst, and Wesleyan Colleges announced similar shifts in admission policy. These early adopters explained that legacy preferences were antithetical to their larger institutional commitments to equity and diversity (as legacy admissions overwhelmingly benefit white students), and Johns Hopkins’ president went so far as to call legacy preference in admissions “nakedly aristocratic.” Fast forward to the present moment, in the wake of last summer’s Supreme Court ruling against affirmative action, these policies are under ever-increased scrutiny. In July 2023, the Education Department opened an investigation into the practice, and schools as diverse as the University of Minnesota, Carleton College, and Bryn Mawr College have recently ended their legacy preferences.

What does that mean for you?

If you are a student planning to apply to your parents’ or grandparents’ alma mater, you do not need to change course. If that school is one of the many great fits you and your College Goals counselor have identified, then stay the course! While you may not receive the extra consideration you once might have, you can still demonstrate your fit for the institution through “Demonstrated Interest” – your supplemental essays, interview (if available), and contact with your admission officer. But like everything in college admission, whether or not your legacy status will help “depends.” There is simply no one rule that applies to all institutions.

The best thing you can do is educate yourself about the practice so you can apply with eyes wide open. To read more, here is a brief Forbes article on The Waning Influence of Legacy College Admissions and for the truly curious, an in-depth report from the Brookings Institution. Finally, this site from Best Colleges includes an updated list by state of colleges who have ended legacy admissions practices as well as a list of those that never used them. We hope you find this helpful!

To SAT? Or, to ACT? How do you pick?

The stress around standardized testing has not gone away despite the shifts that many schools have made toward test-optional admissions. In fact, for some students, the stress around standardized testing seems to have only increased as they consider how to maximize their scores to submit to schools that are test-optional (particularly when those schools seem to have a preference for students to submit high test scores). The specifics around whether “test-optional” really means OPTIONAL is a subject for another blog post. Today, let’s talk about the SAT and the ACT, how they are alike, how they diverge, and how you might be able to choose which test to take without going through the onerous challenge of sitting for both.

First, at the root, the SAT and the ACT really are very similar tests.

Both the SAT and the ACT focus on testing a student’s ability in the key areas of reading, writing, and math. They both ask students to solve problems, read passages, select among multiple-choice answers, and interpret information at a similar level of difficulty. Both the SAT and the ACT provide a standardized means of comparing students despite vastly different high school curriculums and experiences. Contrary to some outdated assumptions, neither the SAT nor the ACT has a “guess penalty” – which means that students should make a guess and answer every question on the test.

The really good news? Most students who take both tests receive a pretty similar score (percentile-wise) on each one.

Despite this, there are some key differences between the SAT and the ACT which might help students decide which test is the “right” test for them.

First, the ACT is a faster-paced test – students are required to answer more questions, per minute, on the ACT than they are on the SAT.

For example –

ACT math = 60 questions, 60 minutes (1 minute per question)

SAT math = 58 questions, 80 minutes (1:23 per question)

ACT English = 75 questions, 45 minutes (36 seconds per question)

SAT writing & language = 44 questions, 35 minutes (48 seconds per question)

ACT reading = 40 questions, 35 minutes (52 seconds per question)

SAT reading = 52 questions, 65 minutes (1:15 per question)

* Note: This applies to the paper-based SAT. The digital SAT (releasing in 2024) will be a shorter test.

SO – If you are a quick processor, someone who often finishes tests in school ahead of the allotted time, the ACT might be a better choice for them. If you prefer to work more slowly through information, or often find yourself using every minute of allotted time, the SAT might be a better fit.

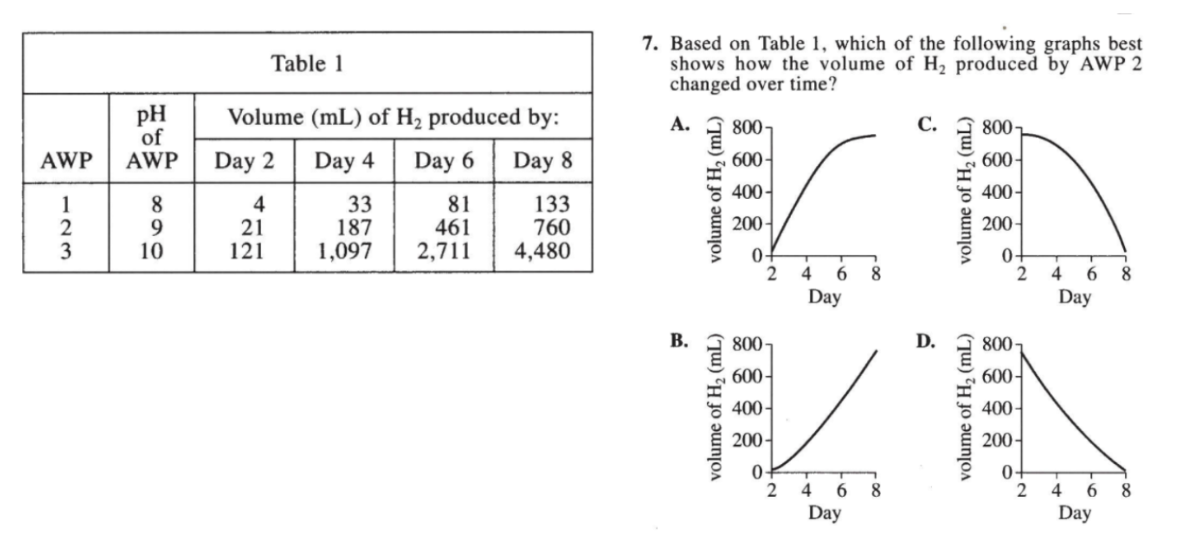

Second, the ACT has a science section. (The SAT does not!)

The science section of the ACT does not really test science concepts. It is really more about logic problems and graph reading. Take a look at this real ACT science question:

What do you think? Does the graph make your head spin? Or does this look like an easy question? (The answer is “B”.) If graph reading is not your thing, no worries, the SAT might be the test for you!

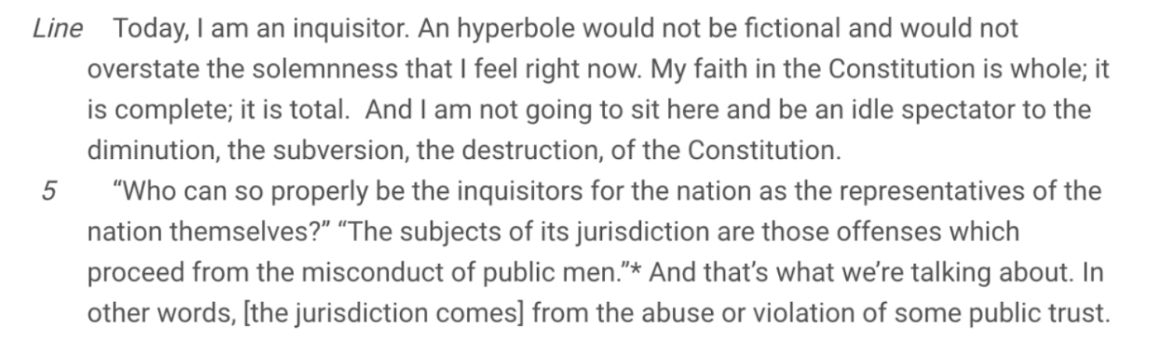

The SAT reading passages tend to be a bit longer, and tricker.

Do you love to read? How’s your vocabulary and ability to parse difficult passages? If you are a bookworm, or someone who loves getting lost in words, the SAT might be a more appealing test for you. Take a look at this real SAT reading passage:

What did you think? If this makes sense to you, maybe the SAT is a good fit test! If you felt lost here, perhaps consider the ACT.

Finally, the SAT has both a “calculator” and “no calculator” math section (only until 2024). For now, the SAT has one math section where students must rely on their mental math abilities. If mental math is not your thing, consider the ACT. However, when the SAT becomes all digital in 2024, the no calculator math section is going away.

The good news? Most of these differences between the tests will continue to be true, even after the SAT switches to digital testing in January 2024. Use some of these guiding questions to decide which test might be a better option for you! And no matter what you select, practice practice practice! There really is no better way to prepare than to be prepared!

It Always Works Out.....

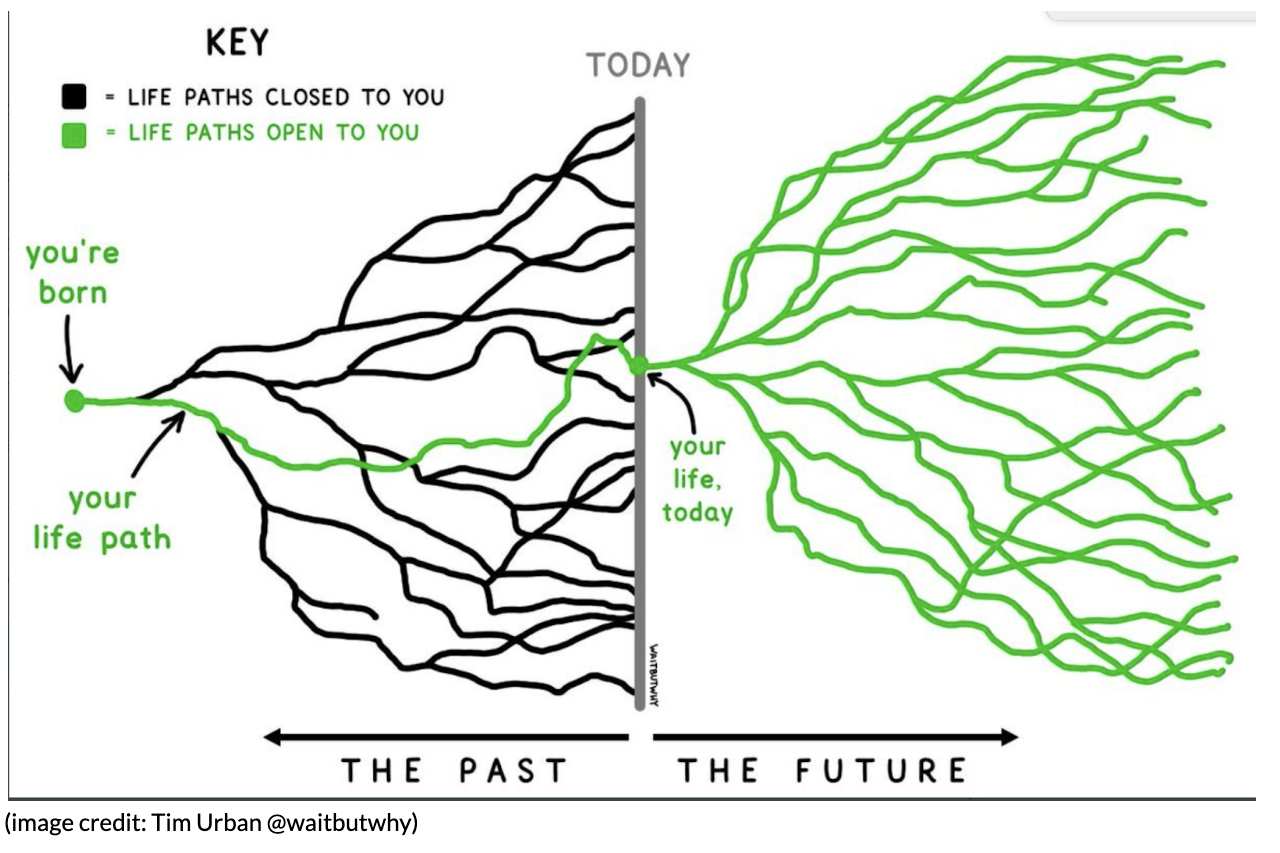

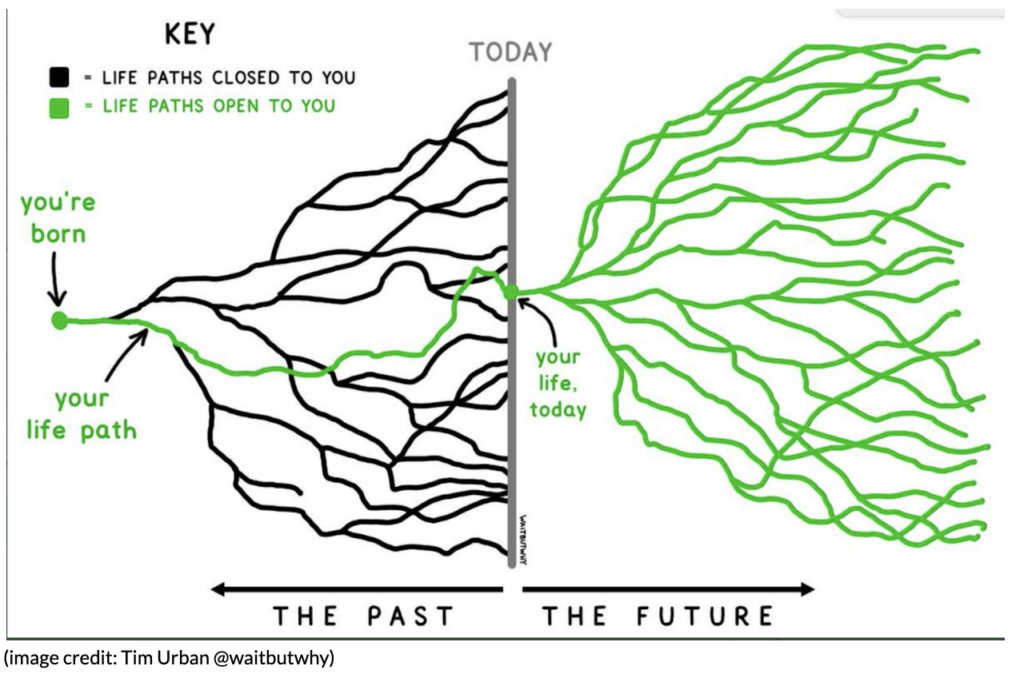

Take a look at this image. No matter who you are, or how old you are, your “today” is just the beginning of an infinite number of possibilities and branching paths.

Having worked as a college counselor for almost two decades, I can say for certain that many students look at their college decision as one of the most influential branches on the path that makes up their life up to that point. Often, when I sit down to meet with a student for the first time in 10th or 11th grade, they have a very specific vision of this path – what school they will attend, what they will study, and where their life will go from there.

Unfortunately, the reality of college admissions is that often these visions (this is the “dream school”; this is the “most perfect major”) do not play themselves out in the process. In the face of some schools receiving more than double the number of applications they received only a few years ago, it is more and more difficult to latch a set of hopes and dreams onto a single school.

But I truly believe that’s exactly as it should be. There should never be just one dream school, or one perfect program. The world is full of infinite paths and options – things students have never imagined or even conceived. Instead of seeing only a single path through the process, I challenge students to see themselves on the green line, and to begin to imagine the vast number of possibilities that lie in front of them.

Therefore, what I most often say to students (and families) throughout the college counseling process is this: “It always works out. It just doesn’t always work out how you think it will right now.”

Consider just a few stories from the Class of 2023:

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was deferred. The student applied to a wide selection of other schools at the regular decision deadline. Ultimately, the Early Decision school admitted the student in March. However, as the student looked at their options, there were others that felt like a better fit. Ultimately, the student enrolled at another school, one that wasn’t on the horizon as even a “high possible choice” in October.

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was rejected. The student continued to research schools all fall and found another school, one that actually might have been a better fit for their interests and plans. The student applied Early Decision II to this new school and was admitted.

- One student applied Early Decision to a school that felt like the best fit for their planned career combining engineering and entrepreneurship. They were rejected. They applied Early Decision II to a second-choice school that also felt like a great fit for this planned future. They were also rejected. Then, the student was admitted to a program within a large public university, one that awards two B.S. degrees (one in engineering, one in business) – a program even more selective than both the ED/ED II schools.

The stories could go on. The theme is simply that the process unfolds in its own way, on its own path. As students (especially rising seniors) approach the college process and begin their applications, it is so important that they keep this fact in mind: there is not only one path (or one school). Thirty years ago, I applied to college intending to major in Biology and head from there to medical school. Instead, I wound up studying philosophy (a subject I had never even heard of before my sophomore year in college) and going into education – a path I could never have conceived at 18.

It always works out – it just doesn’t always work out how you think it’s going to right now.

Choosing Your Courses for the Next Year

Soon, many sophomore and junior students must make choices about their courses for next year. We know the admission process at very selective colleges is based, above all, on your academic performance, and if your grades are not what the college wants to see, your chances of admission will be limited. But how do your curricular choices play out in that process?

Ideally, your college education should have both vertical depth in a single subject and horizontal breadth across many. Admission officers, especially at the most selective colleges, are trying to gauge whether your high school curriculum is equipping you, as a Harvard brochure on preparing for college described it, “with particular skills and information and … a broad perspective on the world and its possibilities.” In fact, most liberal arts colleges are not really admitting students to a particular major (there are exceptions, of course, mostly in pre-professional fields such as engineering and nursing). Thus, choices you make about your curriculum act as a mirror in which they can see your skill/aptitude for pursuing a particular academic interest, but also your curiosity and breadth of mind.

- Are you able to jump into challenging courses in your intended major and make good use of the opportunities on offer? Do you have the math training to take on engineering courses, for example? Do you have the analytical and writing skill to do well in a demanding philosophy course?

- Are you also able and curious to explore beyond your major? Are you flexible enough to see how those “other” ideas might even connect with your field and enrich it? This is as much a practical as a philosophical point. Knowledge is interconnected, and knowing something about statistics, for example, might be very useful to the prospective historian, while a pre-med’s perspective might be shaped by anthropological insights into different cultural assumptions about mind-body connections. In a rapidly changing world, you also don’t know what knowledge the future will require, or which bits of learning will start fading into obsolescence soon after graduation. Your career prospects, therefore, might depend on knowing how to learn, how to analyze critically, and how to communicate your great ideas, whether about a product you are developing or about a public policy you are promoting. You may well have developed some of these skills outside your major!

What does this mean for the courses you should choose in high school, especially if you intend to apply to selective colleges?

- Don’t specialize in high school – if you are mostly not being admitted to a major as a first year, then the fact that you avoided, for example, social science/humanities courses in high school because you intend to study data science, might be a red flag. Note that MIT and Harvey Mudd require applicants to have letters of recommendation from both a STEM teacher AND a humanities/social science one!

- Don’t choose courses because they might be easier, especially if you hope to apply to very selective colleges. Experienced admission officers know that a one-semester government class is likely not going to challenge you as much as AP US History, and that all IB math courses are not equally demanding. As Yale advises its applicants, “Pursue your intellectual interests, so long as it is not at the expense of your program’s overall rigor or your preparedness for college. Be honest with yourself when you are deciding between different courses. Are you choosing a particular course because you are truly excited about it and the challenge it presents, or are you also motivated by a desire to avoid a different academic subject?”

- Choose a course load that will show preparation in a broad academic core, because you will learn important skills and perspectives in each:

- History gives students a better understanding of how the past shapes the present and what is distinctive about our own moment. A rigorous economics course might do the same.

- English will help you write better in a global language and think more critically, while literature gives insight into other lives in different times and places.

- Foreign languages facilitate your access to a global world and to cultures that are not your own. Whether you want to be a businessperson or a physicist, being able to communicate with others and imagine different ways of being and thinking is essential.

- Mathematics not only allows you to balance your checkbook, but also to grasp new scientific discoveries, figure out the economic implications of environmental change, and understand a government’s trade policies. In short, mathematics equips you for modern life.

- Science, in a time when political freedom and environmental health are threatened by false facts and viral conspiracy theories, allows you to analyze scientific concepts and understand their consequences, and think creatively about technology.

- Finally, choose the right rigor for you. Students often ponder whether colleges care most about grades or about rigor. The stock answer is, of course, both. And if you aspire to ultra-selective colleges, this is good advice and a healthy reality check about your chances of admission. But it might not be the most useful advice for every student. NACAC, the national admission organization, counsels you to, “take the most challenging courses that are available and appropriate for you.” So, choose the toughest courses in which, with hard work, you can succeed, and then commit yourself to get as much from them as you can.

The 2022 admission season: what juniors might learn from it

With colleges having announced their 2022 admission decisions, I yet again feel like a recording stuck in a loop as I reiterate to my students that admission at the more selective colleges has become even more challenging. Even so, this year does feel different to me somehow. Perhaps it is the fact that I have seen more amazingly accomplished students who did not get into their dream schools – or indeed even into the ones they deemed target schools – than ever before, that makes the college admission process feel increasingly untenable.

While we wait for waitlists to settle down in coming months, though, a few themes have emerged.

- The University of California’s decisions have left counselors scratching their heads as top academic in-state performers found themselves denied or waitlisted by virtually every UC campus. An article in SF Gate that tracked the UC admit rates over the last 25 years, points out that in 1997 UCLA admitted 36%, UCB 31%, and UCSB, UCI and UCD all around 70%. Today those same schools range from 14% at UCLA and 17% at Berkeley, to 30% at UCI, 37% at UCSB and 46% at UCD. In all cases, Colleges of Engineering admit rates are far below that of each University as a whole.

- Knowing that, in a test-optional world, more kids feel free to apply to more selective colleges, schools are trying to figure what all the uncertainty and turmoil means for their yield, the number of students who will accept their offers. No one wants unfilled dorm beds or overfull classrooms. To help manage that uncertainty, many colleges are filling even a bigger portion of their first-year class with committed Early Decision applicants. The list of colleges that accept more than 50% of their incoming class in Early Decision – Bates, Bowdoin, Claremont, Colby, Haverford, NYU, Northwestern, and many others – is growing. Colleges also waitlist large numbers of applicants, and this year many seniors have found themselves waitlisted even at colleges where they had applied to an early program months earlier.

- Applicants to certain majors seem to have done especially poorly this year, especially in Computer Science, Data Science, Engineering, business and even some life sciences. Presumably this reflects both the huge numbers of applicants attracted to (or pushed towards) fields that seem to promise steady jobs and financial success, as well as the struggles of colleges to meet that surging demand with adequate research and faculty resources (in the five years after 2013/14, for example, the number of CS degrees conferred nationally increased by 60%).

What lessons might current juniors take from all of this?

- Take a healthy reality check from the admit rates. Remember that colleges with single digit admit rates have applicant pools full of strong and accomplished students (far more than they can admit) and the fact that you are one of them means you will be seriously considered. But at the end of the day those schools will admit students based on their limited space and institutional needs. Your college list must reflect the possibility that it might not be you.

- Build your college list on a thoughtful foundation of probable and possible colleges, knowing that a so-called safety is not simply a school to which you will likely be admitted but also one where you will still thrive. The litmus test of admission – if this is the only school to which you were admitted, will you attend – is more important than ever, and many high-performing students found themselves confronted with exactly that outcome.

- Think of your college list less as a series of set categories – probable/safety, possible/target, reach/ultra-reach – than as a dynamic process in which probability shifts according to application timing. Is a college still a target if you apply in Regular Decision, or does it fill so much of its class in Early that the admit rate is halved or even quartered for students applying in Regular Decision?

- Consider your academic narrative in which you explain what you want to study and why you want to do it at any specific college. Most colleges don’t assume you are fixing your major in place when you apply (there are a few exceptions) so discussing your intended major is mostly just an opportunity to show the college the critical depth and analytical skill you have to offer. BUT if the major on your application is in a field that seems overcrowded with applicants, or if it is clear from your limited curiosity that your intended field of study is simply a pathway to a steady job and good paycheck, it makes it harder for admission officers to appreciate what you have to offer academically. (See the recent guest posting on our blog about thinking beyond computer science as a major.)

- And finally, parents come to college admission with assumptions about the process derived from their own experiences and fueled with intense admiration for their children’s hard work and exceptional performances. But it is a different world from the one in which they applied to colleges and it requires new expectations. Thus, in 1990:

- Boston University had 12,400 applicants and admitted 45%. This year it received 80,800 applicants and admitted 14%.

- Northeastern University admitted 97% of its 10,600 applicants. This year, it received 91,000 applicants and admitted 7%.

- Stanford had just under 13,000 applicants and admitted about 22%; last year it received 55,470 applicants and admitted just under 4%.

- Columbia had under 6,000 applicants and admitted 32%; this year the school had over 60,000 applicants and admitted 4%.

- Cornell had about 20,000 applications and admitted about 30%; last year, over 67,000 applied and only 9% made the mark (Cornell is unfortunately one of the colleges that decided this year not to reveal its admission statistics).

- USC admitted a whopping 70% of about 10,000 applicants, bemoaning its declining enrollment; this year, it admitted 12% of the approximately 70,000 applicants.

For many seniors these days, the stress of college admissions feels less like the churning anticipation of preparing for a grand journey, and more like an anxious grind towards misplaced expectations in which much feels beyond one’s control. Perhaps it is only when they accept that their prosperity in life will depend far less on where they choose to attend than on the choices they make once they are on campus, that they will be able to reclaim the adventure.

No, it's not fair!

Every year commentators call on new superlatives to describe the plummeting admit rates at selective colleges. Beset by a growing sense of anxiety about their chances of admission to increasingly rejective colleges, students cast around for explanations in a process that feels increasingly out of their control. “It is not fair,” they say.

They are right, of course, if by fair one means a straightforward, linear application process that rewards clearly defined accomplishments and penalizes equally defined lapses. In fact, college admission has never been “fair” in that sense. After all, how is it fair when some students find that application process easier to navigate than other equally accomplished students, because they have well-educated parents familiar with it? Or when a wealthy family can trade influence and donations for a place at a very selective college? Or when some families can afford a great college education without breaking the bank, while many others, disproportionally students of color, will graduate with crushing debt, if at all?

Perhaps the reason why we want to cast the process within that fair/unfair binary is that it puts the focus on individual students and what they have done and achieved. That allows for a sense of control – if I know that doing X will achieve Y, it becomes within my reach. Doing so, though, misses a very important reality about college admission: it is not simply, or even mostly, about individual students. Rather, it is about the institutional needs of the college.

Listening to families talk, one might assume that an admission office IS the college. But, in reality, the former is simply one piece (albeit an important one!) within a larger institutional whole. As such, it is subject to myriad demands and needs from all corners of that bigger edifice. Does the college’s well-known touring orchestra need a new harpist? Has the anthropology department expanded and would therefore like to see a few more prospective anthropologists? Is the university keen to maintain its status as a liberal arts institution rather than a technical school? Can the institution compete with private industry, and its much higher wages, for enough accomplished computer scientists and biochemists to teach the vast army of STEM applicants? Does the public institution need to accept more out-of-state students because its own state government fails to adequately fund it?

Colleges will address these challenges in many ways. But undergraduate admission is one very significant tool with which to do so. Does this make its admission policies and decisions unfair? It will surely feel so to very diligent high school students who did whatever was asked of them to become a strong candidate and still find themselves turned away by very selective institutions. Their disenchantment is fed by many admission offices that insist that their lack of transparency, even about basic information such as admit rates, is meant to benefit students. (With Penn, Cornell and Princeton joining Stanford in refusing to reveal their admit rates, a shout-out to those folks, like Andy Borst at Illinois and Rick Clark at Georgia Tech, who are working to help pull the curtain back and allow families to see them at work.)

At a moment when higher education is under attack from multiple directions in American society, blunt honesty might be the best marketing strategy of all! Meanwhile, students might want to ponder the fact that when admission officers talk about “holistic” – that magic fig leave of admission speak – the whole in question refers as much to the institution of which an admission office is merely one cog as it does individual students and their contributions.

Waiting on the Waitlist

With college admission decisions made and released, the attention of students and admission officers turns to the tricky challenge of the waitlist. And rarely has the process seemed more chaotic than this year, in which many selective colleges faced higher application numbers, lower admit rates, and greater uncertainty about their yield.

There are many reasons why colleges run waitlists. A waitlist decision acknowledges the good work of strong applicants for whom there wasn’t space in the class. It also helps placate alumni, donors, and faculty whose children were not admitted.

Above all, a waitlist helps a college manage its enrolment numbers. Colleges cannot afford to have empty seats in their first-year class because too many admitted students opted for another offer. But nor do they want double dorm rooms turned into triples because more students than expected accepted their offer. So, they take their best-informed shot – and it is a remarkably good one! – at estimating how many students to admit in excess of the actual number they want in their class.

Even as they decide whom to admit and to deny, though, admission offices also build additional flex into the system by waitlisting many strong applicants. They can, then, in the months after admission decisions are released, continue to add more students to the class if the yield is lower than anticipated. This buffer is especially important in a year such as 2022, when the usual calculations about yield have been blown up by the uncertainty sparked by test-optional admission. By using a waitlist to protect yield, colleges can also pick the candidates that will help them fill gaps in their list of institutional needs – more women mathematicians, oboists, chemical engineers, underrepresented students, first-generation applicants, and so on.

Being waitlisted leaves students in a tough spot. They are happy to remain on the admission radar, but also realize that coming off the waitlist can be a very long shot. In 2020, for example, Chapman in Southern California admitted well over half the students they waitlisted. More typical, however, is the experience at CalTech, which admitted only 10 of the over 300 kids to whom they made a waitlist offer. Or Michigan, which admitted 1,248 students after waitlisting 20,723.

Faced with such odds, what is a waitlisted student to do? The short answer is to continue pursuing the college while also committing to another:

- Make sure you know the deadline for committing to the waitlist, and don’t miss it.

- Note all instructions in the waitlist letter. Does the college encourage you to write an email, submit a note to the admission portal, or tell you unambiguously that they don’t want to hear from you?

- If there are no instructions or if you are encouraged to submit a note, address and email it to the regional admission officer if you know who that is. The more personal your letter, the better! If you don’t have a name, address and email the letter to the Dean of Admission or, as a last resort, to Dear Admission Office at the general undergraduate admission address.

- Be respectful of admission officers’ time constraints and keep the note reasonably short and concise.

- On your way to stating your continued interest, it is okay to express some disappointment, but not frustration or resentment. Better to keep the tone clear, good-humored and optimistic. Being either obsequious or demanding will only alienate the reader.

- Add reference to whatever drew you to the college in the first place – perhaps a particular major, research opportunity or such – to help remind the reader of your thoughtfulness in choosing that school and explain your continued interest.

- If there are any updates to add – an award, an important project completed, or something of which you are particularly proud – tell the reader about it.

- Normally colleges are reluctant to waitlist students who were already deferred from early admission. But, this year, many students find themselves in that position; if this is true for you, feel free to remind the college that your interest has not waned since you first applied.

- Don’t refer to the decisions of other colleges, however. It will play no role in a college’s decision.

Colleges will make waitlist decisions based on their own needs and will likely do so in waves rather than at one set moment. Therefore, the coming months will require resilience and optimism on your part, but also common sense and honesty. You need to visit colleges that have already made you an offer, accept one of those offers (from which you can withdraw if you come off a waitlist), and along the way allow yourself the excitement and joy of this moment. Whatever experience you seek at college, achieving it will depend on the choices you make once on campus, regardless of where that is.

Empathy: Considering another’s perspective in a college application

In preparing their applications to college, high school students are encouraged to be authentic, engaged, passionate, and committed. These are indeed great aspirations, and, hopefully, kids get the message that being true and honest with themselves and putting together a good college application should not be at odds with each other.

One quality usually missing from this list of exhortations, though, might be the most important one: be empathetic. Empathy is a powerful idea whose definition often depends on context. For some, empathy is the same as sympathy, the state of caring for others and “feeling their pain.” It is an emotional response to a shared humanity. “I work in a food pantry for the poor because I feel bad for those who feel hunger; I teach kids how to play basketball because I know how much joy I get from it.” We believe such compassion to be a powerful part of children’s sociality and work to cultivate it. And when colleges ask applicants to write about how they help make the world a better place, it is this kind of empathy that students lay claim to and that admission officers wade through.

In urging students to feel sympathy for those with less privilege than they have, though, we might want to encourage them to do more than feel another’s pain. We also want to suggest a shift in perspective in which they go beyond describing their response towards imagining and interrogating how the other side in this equation feels. Social psychologists call this “perspective taking,” and define it as “the ability to understand how a situation appears to another person and how that person is reacting cognitively and emotionally to the situation.”

Why does this matter to how students present themselves in their college applications? In reading about or listening to how students describe their community service, I am always struck by how they see it as a one-way street: they feel bad for someone who might not have what they do and tell us what they have done to alleviate that need. They rarely seem to realize that there is also another side in this philanthropic equation. The result is variations on the so-called “poor but happy villagers” community service experience that has become so frustrating – and even toxic – to admission officers. They read countless essays about suburban kids teaching, contributing to, and “giving voice” to those who are less privileged. These essays are filled with good intentions but lack even a rudimentary understanding of the inequality and lack of reciprocity in such philanthropic exchanges: the less privileged are merely there to be acted on, to be helped and, hopefully, to be grateful for the assistance.

Don’t misunderstand me. I think such service work can be hugely enriching to a student and can reflect a well-honed sense of social obligation, which I applaud. But we might want to open a conversation with young adults – as parents and as counselors – about what and who is on the other side of that helping hand; to add to their emotional sympathy for the less privileged some of the awareness that comes from a more rational empathy.

Shifting perspective and seeing an exchange from the viewpoint of another, also offers students useful insights about other parts of the application process and, indeed, of life. When students present themselves in essays and interviews, it is often clear that they have not given much thought to who their audience is. It is a one-way conversation: they ascribe to themselves the qualities they feel colleges value (I am determined, helpful, diligent, resilient, keen to help others). It does not occur to them that what they’re trying to say may not be what the other side is hearing! They reference extensive foreign travel, for example, sure that the admission reader will appreciate their global citizenship, when, in fact, the reader hears a blithe catalog of great privilege. And when they describe tutoring an underprivileged fellow student, they rarely consider that admission officers might have been such low-income students themselves — and could find their tone patronizing.

As educational counselors we work in the hope that whatever kids learn from applying to college – about choices and consequences, about good writing – they will bring to bear on other parts of their young lives too. In this, there are few skills more valuable to them than moving from seeing the world strictly through their own eyes, to understanding that in their every interaction with another, there is another viewpoint present too.

Major Myths, Revisited

A recent article by Verónica Leyva takes issue with students paying undue attention to their choice of majors when researching colleges. In Major Myths, Busted, she argues instead for approaching the college search with an open mind, agnostic about any one path towards a degree. There are, after all, countless pathways to many careers, and colleges tend to be more interested in students who are motivated to learn than those narrowly focused on a major.

I think that Ms. Leyva’s arguments are absolutely sound and we should encourage high school students to identify their academic interest – a desire to engage with certain ideas or questions or modes of learning – and not simply a prospective major – an academic basket of courses set by faculty in the field to enable students to reach towards mastery in one discipline.

To the reasons why high school students should not fixate only on their prospective major, I would add the fact that they will likely change their minds anyway! Little point to researching only colleges with outstanding programs in Astrophysics if in the end you might opt to major in Anthropology instead! (I remember fondly a freshman advisee of mine at Brown who came set on studying Physics, before cycling through Philosophy and graduating as a Music major!) As Homer Simpson reminded Lisa, there is a time and a place for everything and it is called college – a time to try new ideas well beyond the narrow prescriptions of high school and challenge your mind beyond your own expectations. And most high school students are so trained to the narrow “boxes” of five core academic disciplines that they have little concept of how those translate into the 100 or more majors of a typical liberal arts university anyway!

There are good reasons for our current pushback against the tyranny of the major in students’ perception of where they should go to college and why. Many counselors have sat with students who, in months past, had lit up as they talked about their passion for the study of history or for the exploration of their favorite solar system. But then college admission comes into play, and suddenly they fixate on applying for the hot major du jour – computer science, chemical engineering, data science. This in spite of the work of economists like Doug Weber, who has shown that while right out of college STEM fields might yield more professional success, they do not inevitably pay better when measured by lifetime earnings.

And yet, having said all this, after twenty years as a college and academic advisor, I have also come to doubt how far we should go in the opposite direction, towards encouraging high school students to ditch all consideration of prospective majors. In part, this is because of the admission process itself (as I noted in a recent post). Majors are the bureaucratic building blocks of an undergraduate degree. Even the majority of liberal arts colleges that allow students to defer declaring a major for a year or two, still ask about intended majors in their applications. A college where the Environmental Studies department has just expanded might well want to make sure that those professors have a gratifyingly large number of prospective majors; and a college where the Classics faculty takes an interest in admission, might well take note of exceptional young Latin scholars.

Moreover, having students think about prospective majors is not at odds with having them identify exciting intellectual reasons for going to college. In fact, seeing how their intellectual interests connect with a particular academic discipline can help give teenagers a scaffolding with which to explore the things they find curious and exciting. I remember, when I first went to university eons ago, how validating it was to realize that people who were experts in the things I was curious about had thought those mattered enough to gather a corpus of knowledge about them and call it a History major! The practitioners of an academic discipline also use their own linguistic conventions to express their questions and concerns – and how liberating for young people to gain insight into that language in order to express their own ideas!

Ultimately though, my point is simply that an American liberal arts education is an extraordinary way of thinking about one’s learning, and students should look at the exciting range of possibilities it offers them, rather than cast around for a narrow academic box to climb into. But college is also not summer camp, and a conversation about majors might be another way to encourage high school students to view their learning with an equally important and exciting search for rigor and intellectual depth.

The Role of Majors in Applying to a Liberal Arts Program

A liberal arts education assumes that students do not commit to any course of study before they are ready to do so. While there are several courses of study, such as engineering and art, where students do apply to a specific course of study, liberal arts applicants to American institutions will at most be asked to state an academic interest. In fact, many colleges require students to declare a major – such as mathematics, economics or sociology – only at the end of sophomore (2nd) year.

Admitting students with little reference to their majors recognizes the fact that they will change their minds as they discover new ideas and new interests. And liberal arts colleges think this is a really good idea! They want students to roam broadly through an interdisciplinary reservoir of knowledge, finding different lenses through which to look at questions that interest them.

It is easy though to confuse this opportunity to explore, with an academic drifting that lacks rigor and discipline. Many college applicants check the box that says they are undecided about an intended major because they are genuinely not ready to commit to a course of study. But others do so because they fail to see that going to college is ultimately an academic choice, not a simple rite of passage, and they are reluctant to think too deeply about what they hope to achieve there. It is a bit like embarking on a trip without having wasted too much thought on either the route or the destination!

More pragmatically, when you apply to selective liberal arts colleges without any thought about your academic direction, you weaken your application. At the very least it makes it harder to give a strong answer when, for example, Cornell asks you “about the areas of study you are excited to explore, and specifically why you wish to pursue them in our College.” Or when you have to “describe how you plan to pursue your academic interests and why you want to explore them at USC specifically.”

Thinking about your major before you apply has other consequences for your application as well. Your chances of admission will not improve because you checked Biology rather than Sociology. But in your explanation of that choice, you give a college the opportunity to gauge your “intellectual vitality.” Compare a student who writes of an interest in how human behavior is conditioned by culture, with one who wants to study Psychology “because my friends always ask me for advice.” Or compare one who limply expresses an interest in Mathematics “because I am good at it,” with a student describing the beauty of Mandelbrot sets. Perhaps a student has in fact been motivated to study Sociology because “I am a social person,” but her answer seems superficial and thoughtless at best, and simply not very smart at worst!

If you wish to persuade a college that you have intellectual depth and curiosity, you need to support your claim with action. Reading, learning from a part-time job, participating in research over the summer, and even engaging with your teachers beyond what a good grade requires are all good ways to develop your academic narrative. And when you research colleges – size, location, clubs – also make time to contemplate, with excitement and anticipation, the academic opportunities that will be at the heart of your college experience.