The 2022 admission season: what juniors might learn from it

With colleges having announced their 2022 admission decisions, I yet again feel like a recording stuck in a loop as I reiterate to my students that admission at the more selective colleges has become even more challenging. Even so, this year does feel different to me somehow. Perhaps it is the fact that I have seen more amazingly accomplished students who did not get into their dream schools – or indeed even into the ones they deemed target schools – than ever before, that makes the college admission process feel increasingly untenable.

While we wait for waitlists to settle down in coming months, though, a few themes have emerged.

- The University of California’s decisions have left counselors scratching their heads as top academic in-state performers found themselves denied or waitlisted by virtually every UC campus. An article in SF Gate that tracked the UC admit rates over the last 25 years, points out that in 1997 UCLA admitted 36%, UCB 31%, and UCSB, UCI and UCD all around 70%. Today those same schools range from 14% at UCLA and 17% at Berkeley, to 30% at UCI, 37% at UCSB and 46% at UCD. In all cases, Colleges of Engineering admit rates are far below that of each University as a whole.

- Knowing that, in a test-optional world, more kids feel free to apply to more selective colleges, schools are trying to figure what all the uncertainty and turmoil means for their yield, the number of students who will accept their offers. No one wants unfilled dorm beds or overfull classrooms. To help manage that uncertainty, many colleges are filling even a bigger portion of their first-year class with committed Early Decision applicants. The list of colleges that accept more than 50% of their incoming class in Early Decision – Bates, Bowdoin, Claremont, Colby, Haverford, NYU, Northwestern, and many others – is growing. Colleges also waitlist large numbers of applicants, and this year many seniors have found themselves waitlisted even at colleges where they had applied to an early program months earlier.

- Applicants to certain majors seem to have done especially poorly this year, especially in Computer Science, Data Science, Engineering, business and even some life sciences. Presumably this reflects both the huge numbers of applicants attracted to (or pushed towards) fields that seem to promise steady jobs and financial success, as well as the struggles of colleges to meet that surging demand with adequate research and faculty resources (in the five years after 2013/14, for example, the number of CS degrees conferred nationally increased by 60%).

What lessons might current juniors take from all of this?

- Take a healthy reality check from the admit rates. Remember that colleges with single digit admit rates have applicant pools full of strong and accomplished students (far more than they can admit) and the fact that you are one of them means you will be seriously considered. But at the end of the day those schools will admit students based on their limited space and institutional needs. Your college list must reflect the possibility that it might not be you.

- Build your college list on a thoughtful foundation of probable and possible colleges, knowing that a so-called safety is not simply a school to which you will likely be admitted but also one where you will still thrive. The litmus test of admission – if this is the only school to which you were admitted, will you attend – is more important than ever, and many high-performing students found themselves confronted with exactly that outcome.

- Think of your college list less as a series of set categories – probable/safety, possible/target, reach/ultra-reach – than as a dynamic process in which probability shifts according to application timing. Is a college still a target if you apply in Regular Decision, or does it fill so much of its class in Early that the admit rate is halved or even quartered for students applying in Regular Decision?

- Consider your academic narrative in which you explain what you want to study and why you want to do it at any specific college. Most colleges don’t assume you are fixing your major in place when you apply (there are a few exceptions) so discussing your intended major is mostly just an opportunity to show the college the critical depth and analytical skill you have to offer. BUT if the major on your application is in a field that seems overcrowded with applicants, or if it is clear from your limited curiosity that your intended field of study is simply a pathway to a steady job and good paycheck, it makes it harder for admission officers to appreciate what you have to offer academically. (See the recent guest posting on our blog about thinking beyond computer science as a major.)

- And finally, parents come to college admission with assumptions about the process derived from their own experiences and fueled with intense admiration for their children’s hard work and exceptional performances. But it is a different world from the one in which they applied to colleges and it requires new expectations. Thus, in 1990:

- Boston University had 12,400 applicants and admitted 45%. This year it received 80,800 applicants and admitted 14%.

- Northeastern University admitted 97% of its 10,600 applicants. This year, it received 91,000 applicants and admitted 7%.

- Stanford had just under 13,000 applicants and admitted about 22%; last year it received 55,470 applicants and admitted just under 4%.

- Columbia had under 6,000 applicants and admitted 32%; this year the school had over 60,000 applicants and admitted 4%.

- Cornell had about 20,000 applications and admitted about 30%; last year, over 67,000 applied and only 9% made the mark (Cornell is unfortunately one of the colleges that decided this year not to reveal its admission statistics).

- USC admitted a whopping 70% of about 10,000 applicants, bemoaning its declining enrollment; this year, it admitted 12% of the approximately 70,000 applicants.

For many seniors these days, the stress of college admissions feels less like the churning anticipation of preparing for a grand journey, and more like an anxious grind towards misplaced expectations in which much feels beyond one’s control. Perhaps it is only when they accept that their prosperity in life will depend far less on where they choose to attend than on the choices they make once they are on campus, that they will be able to reclaim the adventure.

A career in software computing? Consider a major other than CS

Guest Blogger, Sam Fisher

Applying to college seems to get harder every year, and the only thing even tougher is applying to college as a prospective computer science major. A New York Times article noted, for example, that in 2019 more than 3,300 incoming first-year students at UT Austin sought computer science as their first choice of major, which was more than double the number who did so five years earlier. The same year, and in response to a reality in which some 20% of Stanford undergraduate degrees are conferred in CS, The Stanford Daily published an article on “CS in Crisis.”

No wonder many prospective first years are fearful about their chances of admission to a top CS program! But it’s not all bad news. As someone who’s done this myself and knows many others like me, I am here to tell you that majoring in computer science is not the only way to get into software engineering (or other top jobs in tech). And, in my opinion, it’s not even the best way.

It may surprise you to hear that, to be a successful software engineer out of college, it likely only requires you to take around five computer science classes while in school. In those five or so classes (let’s say 2-3 core classes teaching you the fundamentals of coding and 2-3 electives in an area you find interesting), you can develop all of the fundamentals you need to kick off your career. Those classes are essential, so don’t skimp out on them, and furthermore, I recommend taking them as early in college as you can.

Once you get beyond those core classes that teach you the fundamentals of how to write code, most of your gains in developing your skills as a software engineer will come from side projects and on-the-job training. Side projects are easy to find. Work on them with your friends, if possible, and treat them like real-world projects. Even if it’s overkill for those projects, try to use Source Control like Github or Gitlab, and try deploying them to a cloud provider through a free trial or student credit programs. You’ll gain key knowledge in places where many computer science majors even fall short, and it’ll help you stand out in your internships and job interviews.

So what classes should you take, and what should you consider majoring in? The short answer: anything you find interesting. Have you always been interested in psychology? Maybe major in that. Or perhaps you love learning new languages and cultures, so you major in Spanish and study abroad in Latin America? Or maybe you’ve always been interested in sciences, and you’ll explore biology, chemistry, or environmental sciences in your first few years before deciding on a major.

And what would those majors do for you if you chose them? Beyond the core value of teaching you how to think and helping your mind grow, you might develop expertise that helps you in your first coding job, or whatever early career you choose.

Let’s say you chose that psychology major; it could make you much more attuned to user experience and how people learn, key skills in user-centered app development, product management, and product design. What if you chose the Spanish major? You could build out a start-up in one of the fastest-growing, low-cost coding hubs in the region like Bogota, and have a cultural leg-up in understanding their labor market and consumer preferences. Finally, if you majored in biology, you could have an enormous advantage applying to be an engineer in the biotech space, working for a company like 23andme or the next great startup.

The world is short on talented computer scientists right now, but even more so, it’s short on people with expertise and passion in their field with enough computer science knowledge to be effective. Those are the people who will be the biggest winners and make the most impact.

Sam Fisher is a senior product manager at Oracle Cloud and graduated from Stanford with a BS in Symbolic Systems in 2014 and an MBA in 2019.

No, it's not fair!

Every year commentators call on new superlatives to describe the plummeting admit rates at selective colleges. Beset by a growing sense of anxiety about their chances of admission to increasingly rejective colleges, students cast around for explanations in a process that feels increasingly out of their control. “It is not fair,” they say.

They are right, of course, if by fair one means a straightforward, linear application process that rewards clearly defined accomplishments and penalizes equally defined lapses. In fact, college admission has never been “fair” in that sense. After all, how is it fair when some students find that application process easier to navigate than other equally accomplished students, because they have well-educated parents familiar with it? Or when a wealthy family can trade influence and donations for a place at a very selective college? Or when some families can afford a great college education without breaking the bank, while many others, disproportionally students of color, will graduate with crushing debt, if at all?

Perhaps the reason why we want to cast the process within that fair/unfair binary is that it puts the focus on individual students and what they have done and achieved. That allows for a sense of control – if I know that doing X will achieve Y, it becomes within my reach. Doing so, though, misses a very important reality about college admission: it is not simply, or even mostly, about individual students. Rather, it is about the institutional needs of the college.

Listening to families talk, one might assume that an admission office IS the college. But, in reality, the former is simply one piece (albeit an important one!) within a larger institutional whole. As such, it is subject to myriad demands and needs from all corners of that bigger edifice. Does the college’s well-known touring orchestra need a new harpist? Has the anthropology department expanded and would therefore like to see a few more prospective anthropologists? Is the university keen to maintain its status as a liberal arts institution rather than a technical school? Can the institution compete with private industry, and its much higher wages, for enough accomplished computer scientists and biochemists to teach the vast army of STEM applicants? Does the public institution need to accept more out-of-state students because its own state government fails to adequately fund it?

Colleges will address these challenges in many ways. But undergraduate admission is one very significant tool with which to do so. Does this make its admission policies and decisions unfair? It will surely feel so to very diligent high school students who did whatever was asked of them to become a strong candidate and still find themselves turned away by very selective institutions. Their disenchantment is fed by many admission offices that insist that their lack of transparency, even about basic information such as admit rates, is meant to benefit students. (With Penn, Cornell and Princeton joining Stanford in refusing to reveal their admit rates, a shout-out to those folks, like Andy Borst at Illinois and Rick Clark at Georgia Tech, who are working to help pull the curtain back and allow families to see them at work.)

At a moment when higher education is under attack from multiple directions in American society, blunt honesty might be the best marketing strategy of all! Meanwhile, students might want to ponder the fact that when admission officers talk about “holistic” – that magic fig leave of admission speak – the whole in question refers as much to the institution of which an admission office is merely one cog as it does individual students and their contributions.

Waiting on the Waitlist

With college admission decisions made and released, the attention of students and admission officers turns to the tricky challenge of the waitlist. And rarely has the process seemed more chaotic than this year, in which many selective colleges faced higher application numbers, lower admit rates, and greater uncertainty about their yield.

There are many reasons why colleges run waitlists. A waitlist decision acknowledges the good work of strong applicants for whom there wasn’t space in the class. It also helps placate alumni, donors, and faculty whose children were not admitted.

Above all, a waitlist helps a college manage its enrolment numbers. Colleges cannot afford to have empty seats in their first-year class because too many admitted students opted for another offer. But nor do they want double dorm rooms turned into triples because more students than expected accepted their offer. So, they take their best-informed shot – and it is a remarkably good one! – at estimating how many students to admit in excess of the actual number they want in their class.

Even as they decide whom to admit and to deny, though, admission offices also build additional flex into the system by waitlisting many strong applicants. They can, then, in the months after admission decisions are released, continue to add more students to the class if the yield is lower than anticipated. This buffer is especially important in a year such as 2022, when the usual calculations about yield have been blown up by the uncertainty sparked by test-optional admission. By using a waitlist to protect yield, colleges can also pick the candidates that will help them fill gaps in their list of institutional needs – more women mathematicians, oboists, chemical engineers, underrepresented students, first-generation applicants, and so on.

Being waitlisted leaves students in a tough spot. They are happy to remain on the admission radar, but also realize that coming off the waitlist can be a very long shot. In 2020, for example, Chapman in Southern California admitted well over half the students they waitlisted. More typical, however, is the experience at CalTech, which admitted only 10 of the over 300 kids to whom they made a waitlist offer. Or Michigan, which admitted 1,248 students after waitlisting 20,723.

Faced with such odds, what is a waitlisted student to do? The short answer is to continue pursuing the college while also committing to another:

- Make sure you know the deadline for committing to the waitlist, and don’t miss it.

- Note all instructions in the waitlist letter. Does the college encourage you to write an email, submit a note to the admission portal, or tell you unambiguously that they don’t want to hear from you?

- If there are no instructions or if you are encouraged to submit a note, address and email it to the regional admission officer if you know who that is. The more personal your letter, the better! If you don’t have a name, address and email the letter to the Dean of Admission or, as a last resort, to Dear Admission Office at the general undergraduate admission address.

- Be respectful of admission officers’ time constraints and keep the note reasonably short and concise.

- On your way to stating your continued interest, it is okay to express some disappointment, but not frustration or resentment. Better to keep the tone clear, good-humored and optimistic. Being either obsequious or demanding will only alienate the reader.

- Add reference to whatever drew you to the college in the first place – perhaps a particular major, research opportunity or such – to help remind the reader of your thoughtfulness in choosing that school and explain your continued interest.

- If there are any updates to add – an award, an important project completed, or something of which you are particularly proud – tell the reader about it.

- Normally colleges are reluctant to waitlist students who were already deferred from early admission. But, this year, many students find themselves in that position; if this is true for you, feel free to remind the college that your interest has not waned since you first applied.

- Don’t refer to the decisions of other colleges, however. It will play no role in a college’s decision.

Colleges will make waitlist decisions based on their own needs and will likely do so in waves rather than at one set moment. Therefore, the coming months will require resilience and optimism on your part, but also common sense and honesty. You need to visit colleges that have already made you an offer, accept one of those offers (from which you can withdraw if you come off a waitlist), and along the way allow yourself the excitement and joy of this moment. Whatever experience you seek at college, achieving it will depend on the choices you make once on campus, regardless of where that is.

Empathy: Considering another’s perspective in a college application

In preparing their applications to college, high school students are encouraged to be authentic, engaged, passionate, and committed. These are indeed great aspirations, and, hopefully, kids get the message that being true and honest with themselves and putting together a good college application should not be at odds with each other.

One quality usually missing from this list of exhortations, though, might be the most important one: be empathetic. Empathy is a powerful idea whose definition often depends on context. For some, empathy is the same as sympathy, the state of caring for others and “feeling their pain.” It is an emotional response to a shared humanity. “I work in a food pantry for the poor because I feel bad for those who feel hunger; I teach kids how to play basketball because I know how much joy I get from it.” We believe such compassion to be a powerful part of children’s sociality and work to cultivate it. And when colleges ask applicants to write about how they help make the world a better place, it is this kind of empathy that students lay claim to and that admission officers wade through.

In urging students to feel sympathy for those with less privilege than they have, though, we might want to encourage them to do more than feel another’s pain. We also want to suggest a shift in perspective in which they go beyond describing their response towards imagining and interrogating how the other side in this equation feels. Social psychologists call this “perspective taking,” and define it as “the ability to understand how a situation appears to another person and how that person is reacting cognitively and emotionally to the situation.”

Why does this matter to how students present themselves in their college applications? In reading about or listening to how students describe their community service, I am always struck by how they see it as a one-way street: they feel bad for someone who might not have what they do and tell us what they have done to alleviate that need. They rarely seem to realize that there is also another side in this philanthropic equation. The result is variations on the so-called “poor but happy villagers” community service experience that has become so frustrating – and even toxic – to admission officers. They read countless essays about suburban kids teaching, contributing to, and “giving voice” to those who are less privileged. These essays are filled with good intentions but lack even a rudimentary understanding of the inequality and lack of reciprocity in such philanthropic exchanges: the less privileged are merely there to be acted on, to be helped and, hopefully, to be grateful for the assistance.

Don’t misunderstand me. I think such service work can be hugely enriching to a student and can reflect a well-honed sense of social obligation, which I applaud. But we might want to open a conversation with young adults – as parents and as counselors – about what and who is on the other side of that helping hand; to add to their emotional sympathy for the less privileged some of the awareness that comes from a more rational empathy.

Shifting perspective and seeing an exchange from the viewpoint of another, also offers students useful insights about other parts of the application process and, indeed, of life. When students present themselves in essays and interviews, it is often clear that they have not given much thought to who their audience is. It is a one-way conversation: they ascribe to themselves the qualities they feel colleges value (I am determined, helpful, diligent, resilient, keen to help others). It does not occur to them that what they’re trying to say may not be what the other side is hearing! They reference extensive foreign travel, for example, sure that the admission reader will appreciate their global citizenship, when, in fact, the reader hears a blithe catalog of great privilege. And when they describe tutoring an underprivileged fellow student, they rarely consider that admission officers might have been such low-income students themselves — and could find their tone patronizing.

As educational counselors we work in the hope that whatever kids learn from applying to college – about choices and consequences, about good writing – they will bring to bear on other parts of their young lives too. In this, there are few skills more valuable to them than moving from seeing the world strictly through their own eyes, to understanding that in their every interaction with another, there is another viewpoint present too.

The Advantages of Boarding School

Students who attend boarding school get to live, learn, and thrive with motivated peers from around the world, supported by compassionate and dedicated faculty who serve as teachers, coaches, and dorm parents. At boarding school, students wake up each morning in a community buzzing with energy and know they are part of something special and unique.

LIVE

Life at boarding school is exciting and full of possibilities. Boarding school students report spending more time engaging with their communities and exploring their passions than students at private day schools and public schools[1]. Since students live and work alongside each other and the faculty every day, from the stage to the studio to the field, students have nearly endless options for immersing themselves in their interests and discovering new ones.

Along the way, students form meaningful relationships with caring educators who offer inspiration, guidance, and motivation. Coaches, teachers, and dorm parents are committed to creating supportive, nurturing environments where students feel inspired to grow as learners, members of the community, and leaders. In fact, 77% of boarding school students say that boarding school gives them the opportunity to lead[2].

LEARN

Going to class at boarding school is inspiring. Not only do students learn from high-quality teachers, but students also report being surrounded by motivated peers, making the learning environment rich and rewarding. Students’ classmates are also their teammates, bandmates, and roommates — so the learning doesn’t stop at the classroom door. Exciting and engaging conversations happen in dorm common rooms, fueled by snacks made by dorm parents.

Students feel academically challenged at boarding school. Small class size and easy access to faculty outside of the academic day allow students individualized attention so that they can also feel supported on their rigorous academic journeys. Teachers meet with students one-on-one to review everything from math concepts to essay writing techniques. At boarding school, students are both challenged and supported and feel intellectually inspired and academically satisfied.

THRIVE

Ready to face the challenges of college and beyond, boarding school students are prepared to thrive in the world after high school. Living on campus, learning with motivated peers, and engaging in leadership opportunities are just a few of the ways that boarding school sets students up for success. A majority of boarding school students report feeling prepared to succeed in college.

When asked if they would go to boarding school all over again, 90% of graduates said yes! At boarding school, students develop self-motivation, independence, and the ability to think critically and creatively. These skills not only help with college readiness, but they also set the foundation for career success later in life. Boarding school — and all that it has to offer — is an experience that lasts for a lifetime.

[1] Begin the Adventure of Your Life, © Copyright 2009-2019 The Association of Boarding Schools

[2] Begin the Adventure of Your Life, © Copyright 2009-2019 The Association of Boarding Schools

How Heavy Is Your Backpack?

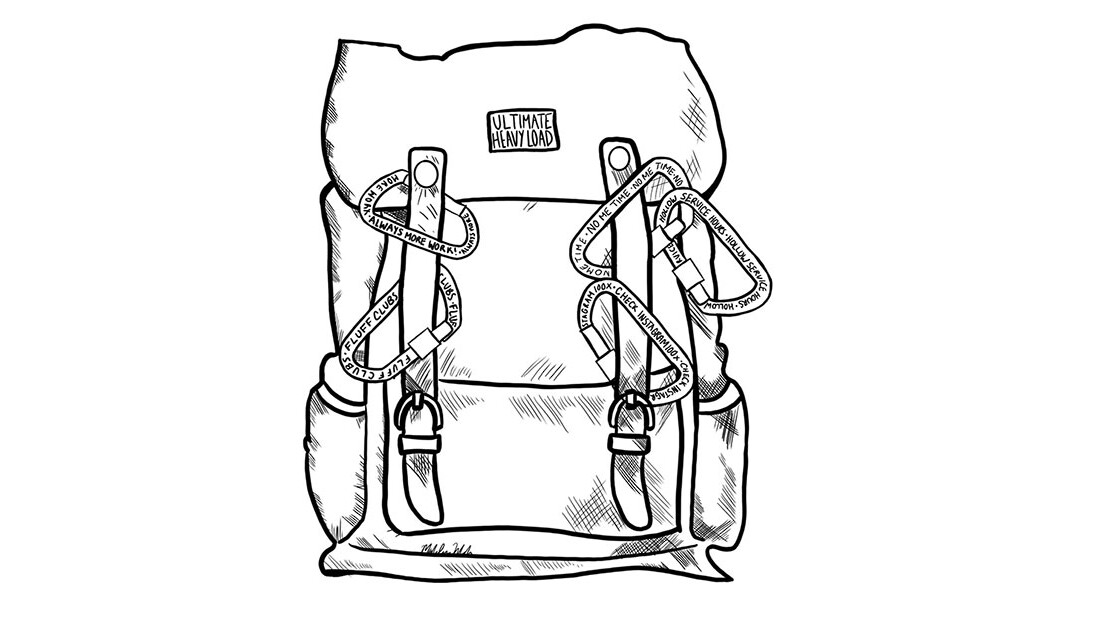

While I was walking through the snow (yes … we still get snow in March in Rhode Island) with one of my best friends a few weeks ago, she began telling me about a coaching framework she’s been working on—centered around a backpack. My friend Brountas (I call her by her last name … something that stuck during our college years together) owns an executive coaching business (https://www.linkedin.com/in/jen-brountas-16b731/). She uses the backpack analogy as a way to help her clients prioritize the things occupying their headspace. A backpack is a useful tool, but it has a limited capacity and a tendency to collect stuff that weighs you down. I couldn’t help but think that her framework and analogy could benefit my students as they transition into a post-pandemic world.

Brountas described her backpack idea as a way to talk about what feels awful and what feels good in our lives, and the consequences of letting the best parts of ourselves get lost in the load. I think a lot of my students would agree that the weight of junior and senior year of high school can “feel awful and overwhelming ” just like the weight of a too-heavy backpack. Everything about these later years of high school feels important … there is so much pressure to have just as heavy a backpack as everyone else, especially when thinking ahead to college. In fact, students often tend to “clip on” more responsibilities, like carabiners that create more weight on their shoulders.

“Think about what you miss and don’t miss” is a phrase I’ve heard many times over the course of the last year. I think most of us can quickly rattle off a few things we’ve missed throughout the pandemic and others we would happily toss out of our bags. It’s fun taking the time to reflect, but it’s much harder to actually leave some of your old life behind—to physically remove the weight or change the way you engage with the items that gnaw at your side. This spring, don’t just think about what’s next; instead, take action and make the leap forward to make your high school years the best they can be. A “big” bag full of all the right “things” doesn’t need to be heavy.

Stop & Unpack:

What “Rona” (as my students like to call the virus) did was force you to stop. It forced you to put aside your heavy load for a while. As Brountas says, “Feel the release. Step away from the bag and be conscious of what’s going on so that you can have a fresh perspective.” Before you sling the heavy bag back on your shoulders, I encourage you to unpack each item and sift out the “trash.” Is sitting on the bench at your team’s games getting you down? Maybe let that go and pick up something that makes you feel lighter and better represents the person you’re becoming.

Sort:

Sort the commitments in your life into categories: activities, clubs, the classes you’ve signed up for, jobs, internships, projects, time for sleep, time with friends and family, etc. What means the most to you? What would you like to leave behind? This act of reprioritizing isn’t something you should be ashamed of, it’s something you’ll have to do for the rest of your life. You’re just setting new goals!

Repack:

What do you want to take with you from the pandemic? Did you learn new skills? Strengthen your work ethic and confidence? Include these intangibles with your other priorities and make sure you have enough space — the type of space you enjoyed in your life as your heavy commitments shut down this year.

Try It On:

How does it feel? Is it still heavy in one area? Uncomfortably rubbing your side? If so, be aware of the irritating item in there that might need some reshifting. Maybe you just need to look at it differently? Perhaps a slight adjustment, like taking on a different role, forming a study group, or asking friends to join you in an activity can help make it feel more comfortable in your bag.

As schools go back to in-person learning, let’s talk through your re-entry and what’s most important — so that you don’t tip over from too heavy a bag. I believe a strong college application is closely tied to the joy and personal growth that comes from making good choices, and as Brountas says, “Monitor your backpack’s framework: it should be powerful and effective but not overwhelming.” An ideal weight, without filling your bag to the brim, allows you to walk with confidence and more intentionality as you move through your days and put time into what matters most to you.

Major Myths, Revisited

A recent article by Verónica Leyva takes issue with students paying undue attention to their choice of majors when researching colleges. In Major Myths, Busted, she argues instead for approaching the college search with an open mind, agnostic about any one path towards a degree. There are, after all, countless pathways to many careers, and colleges tend to be more interested in students who are motivated to learn than those narrowly focused on a major.

I think that Ms. Leyva’s arguments are absolutely sound and we should encourage high school students to identify their academic interest – a desire to engage with certain ideas or questions or modes of learning – and not simply a prospective major – an academic basket of courses set by faculty in the field to enable students to reach towards mastery in one discipline.

To the reasons why high school students should not fixate only on their prospective major, I would add the fact that they will likely change their minds anyway! Little point to researching only colleges with outstanding programs in Astrophysics if in the end you might opt to major in Anthropology instead! (I remember fondly a freshman advisee of mine at Brown who came set on studying Physics, before cycling through Philosophy and graduating as a Music major!) As Homer Simpson reminded Lisa, there is a time and a place for everything and it is called college – a time to try new ideas well beyond the narrow prescriptions of high school and challenge your mind beyond your own expectations. And most high school students are so trained to the narrow “boxes” of five core academic disciplines that they have little concept of how those translate into the 100 or more majors of a typical liberal arts university anyway!

There are good reasons for our current pushback against the tyranny of the major in students’ perception of where they should go to college and why. Many counselors have sat with students who, in months past, had lit up as they talked about their passion for the study of history or for the exploration of their favorite solar system. But then college admission comes into play, and suddenly they fixate on applying for the hot major du jour – computer science, chemical engineering, data science. This in spite of the work of economists like Doug Weber, who has shown that while right out of college STEM fields might yield more professional success, they do not inevitably pay better when measured by lifetime earnings.

And yet, having said all this, after twenty years as a college and academic advisor, I have also come to doubt how far we should go in the opposite direction, towards encouraging high school students to ditch all consideration of prospective majors. In part, this is because of the admission process itself (as I noted in a recent post). Majors are the bureaucratic building blocks of an undergraduate degree. Even the majority of liberal arts colleges that allow students to defer declaring a major for a year or two, still ask about intended majors in their applications. A college where the Environmental Studies department has just expanded might well want to make sure that those professors have a gratifyingly large number of prospective majors; and a college where the Classics faculty takes an interest in admission, might well take note of exceptional young Latin scholars.

Moreover, having students think about prospective majors is not at odds with having them identify exciting intellectual reasons for going to college. In fact, seeing how their intellectual interests connect with a particular academic discipline can help give teenagers a scaffolding with which to explore the things they find curious and exciting. I remember, when I first went to university eons ago, how validating it was to realize that people who were experts in the things I was curious about had thought those mattered enough to gather a corpus of knowledge about them and call it a History major! The practitioners of an academic discipline also use their own linguistic conventions to express their questions and concerns – and how liberating for young people to gain insight into that language in order to express their own ideas!

Ultimately though, my point is simply that an American liberal arts education is an extraordinary way of thinking about one’s learning, and students should look at the exciting range of possibilities it offers them, rather than cast around for a narrow academic box to climb into. But college is also not summer camp, and a conversation about majors might be another way to encourage high school students to view their learning with an equally important and exciting search for rigor and intellectual depth.

The Role of Majors in Applying to a Liberal Arts Program

A liberal arts education assumes that students do not commit to any course of study before they are ready to do so. While there are several courses of study, such as engineering and art, where students do apply to a specific course of study, liberal arts applicants to American institutions will at most be asked to state an academic interest. In fact, many colleges require students to declare a major – such as mathematics, economics or sociology – only at the end of sophomore (2nd) year.

Admitting students with little reference to their majors recognizes the fact that they will change their minds as they discover new ideas and new interests. And liberal arts colleges think this is a really good idea! They want students to roam broadly through an interdisciplinary reservoir of knowledge, finding different lenses through which to look at questions that interest them.

It is easy though to confuse this opportunity to explore, with an academic drifting that lacks rigor and discipline. Many college applicants check the box that says they are undecided about an intended major because they are genuinely not ready to commit to a course of study. But others do so because they fail to see that going to college is ultimately an academic choice, not a simple rite of passage, and they are reluctant to think too deeply about what they hope to achieve there. It is a bit like embarking on a trip without having wasted too much thought on either the route or the destination!

More pragmatically, when you apply to selective liberal arts colleges without any thought about your academic direction, you weaken your application. At the very least it makes it harder to give a strong answer when, for example, Cornell asks you “about the areas of study you are excited to explore, and specifically why you wish to pursue them in our College.” Or when you have to “describe how you plan to pursue your academic interests and why you want to explore them at USC specifically.”

Thinking about your major before you apply has other consequences for your application as well. Your chances of admission will not improve because you checked Biology rather than Sociology. But in your explanation of that choice, you give a college the opportunity to gauge your “intellectual vitality.” Compare a student who writes of an interest in how human behavior is conditioned by culture, with one who wants to study Psychology “because my friends always ask me for advice.” Or compare one who limply expresses an interest in Mathematics “because I am good at it,” with a student describing the beauty of Mandelbrot sets. Perhaps a student has in fact been motivated to study Sociology because “I am a social person,” but her answer seems superficial and thoughtless at best, and simply not very smart at worst!

If you wish to persuade a college that you have intellectual depth and curiosity, you need to support your claim with action. Reading, learning from a part-time job, participating in research over the summer, and even engaging with your teachers beyond what a good grade requires are all good ways to develop your academic narrative. And when you research colleges – size, location, clubs – also make time to contemplate, with excitement and anticipation, the academic opportunities that will be at the heart of your college experience.

The Role of Parents in the College Application Process

My husband and I live on a college campus where he is a professor. Over the years we have spent many entertaining moments watching families of prospective students doing the college visit – teenagers lagging behind pretending they do not know their parents, mothers excited about the grand adventure but fretting about the imminent pain of rejection, fathers equally enthusiastic but wondering if the place really warrants that exorbitant price tag. It ceased to be quite so amusing when we became one of those families ourselves!

College admissions present parents with difficult ethical, social and educational choices. We want our children to enjoy the adventure, act with integrity, feel good about the outcome, and be launched into successful and empowered adulthood under their own steam. Yet, we also witness the avalanche of requirements bearing down on them and we listen to other parents stressing about declining admit rates and soaring college expectations. In the end, many parents feel like they need to choose between allowing their teenagers the space to forge their own way to college or, given the stress and complexities of the process, usurping their child’s ability and right to retain ownership of it. The road to helicopter parenting is, like the one to hell, paved with the best of intentions!

There are no clear or easy answers to managing the application process well as a parent. But here are a few tips towards being appropriately and productively involved in your child’s college application:

- You are their foremost model for how to deal with the stress, disappointments and joys of this process. It is not necessarily what you say but what you do that will likely have the greatest impact on their behavior and perspective.

- Help your child develop the tools to evaluate colleges sensibly and thoughtfully – if you cannot move your own thinking beyond superficialities of rank and status, it will be hard for your child to engage constructively with the idea of a good college “fit.” If they don’t understand that what they do at college matters more than the rank of the school they got into, you might spend four more years worrying about the fact that being a mediocre or unhappy student at a highly ranked institution will probably not do for their futures what you had hoped it would! Remind your child – and yourself – that the college application process is only the opening act to the more important drama of succeeding at college.

- The only thing perhaps more counterproductive these days than a helicoptering parent, is a snowploughing one! To be successful, students need self-motivation, independence and self-reliance in the absence of a parent herding them along. Admission officers always note at information sessions how parents ask all the questions. Resist! Give your child the opportunity – and the responsibility – to ask their own questions, make their own calls, and organize their own calendars.

- Help set up campus visits, and then work at making these pleasant and instructive experiences for all. This requires that you bite your tongue when they express opinions that are thoughtless or even silly; keep your temper when they announce on arrival that this is not a good place for them; and listen for the subtext when they are having trouble articulating their dreams and anxieties. And remember to enjoy what may be your last extended trip with your teenager!

- Overcome your reluctance to talk to them about money. College is expensive and there are few moments sadder than when families realize that getting admitted to a dream school is not enough to make the dream come true. This can be avoided if your family talks about what is affordable or beyond your means, and think about how to put the unattainable within reach. The financial aid process is largely in the hands of parents, so be organized about it. Do your taxes early, inform yourselves about requirements, and complete the applications in a timely manner.

- Step away from that college essay! It is not yours to write, and in forgetting that fact you are not doing your child any favors. Essays written by parents often sound like it – smoothly written, adult in tone, and simply not very interesting. And if you do not model ethical behavior, will your child know that at college submitting another’s work as their own will get them ejected? And, more importantly, how can they have confidence in their own ideas when you show them that you don’t? But if they do ask you for essay ideas or comments, savor their trust in you and be supportive, thoughtful and gently honest.

Above all, help your teenagers develop a healthy perspective on this process by reminding them that your unconditional love does not depend on ivy growing on their colleges’ walls! As parents, we assume they know this. Yet this is a moment most likely to test their confidence and sense of self. But it is also a great opportunity for you to put finishing touches to the job you started 18 years earlier, and to send them off into the world knowing that whatever the outcome of their college application, you value them.