It Always Works Out.....

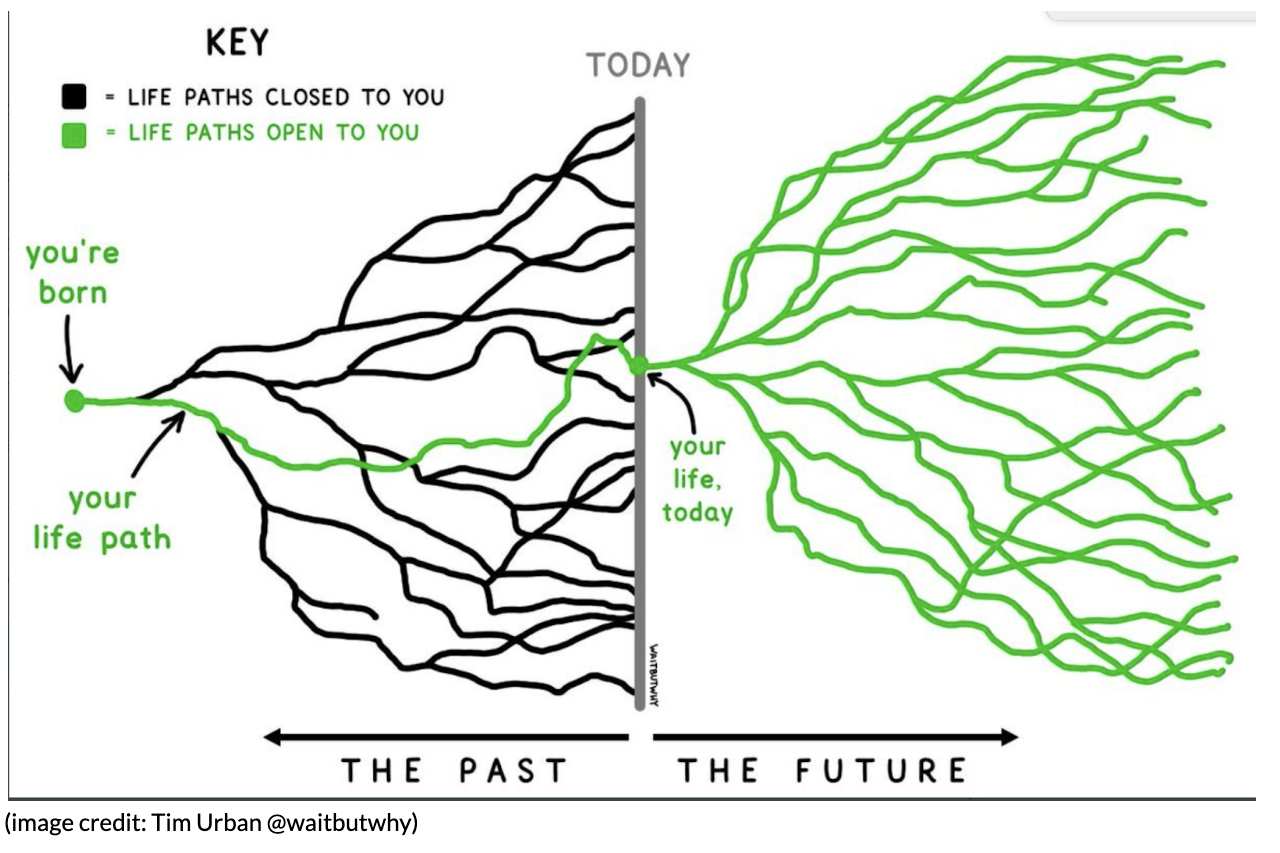

Take a look at this image. No matter who you are, or how old you are, your “today” is just the beginning of an infinite number of possibilities and branching paths.

Having worked as a college counselor for almost two decades, I can say for certain that many students look at their college decision as one of the most influential branches on the path that makes up their life up to that point. Often, when I sit down to meet with a student for the first time in 10th or 11th grade, they have a very specific vision of this path – what school they will attend, what they will study, and where their life will go from there.

Unfortunately, the reality of college admissions is that often these visions (this is the “dream school”; this is the “most perfect major”) do not play themselves out in the process. In the face of some schools receiving more than double the number of applications they received only a few years ago, it is more and more difficult to latch a set of hopes and dreams onto a single school.

But I truly believe that’s exactly as it should be. There should never be just one dream school, or one perfect program. The world is full of infinite paths and options – things students have never imagined or even conceived. Instead of seeing only a single path through the process, I challenge students to see themselves on the green line, and to begin to imagine the vast number of possibilities that lie in front of them.

Therefore, what I most often say to students (and families) throughout the college counseling process is this: “It always works out. It just doesn’t always work out how you think it will right now.”

Consider just a few stories from the Class of 2023:

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was deferred. The student applied to a wide selection of other schools at the regular decision deadline. Ultimately, the Early Decision school admitted the student in March. However, as the student looked at their options, there were others that felt like a better fit. Ultimately, the student enrolled at another school, one that wasn’t on the horizon as even a “high possible choice” in October.

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was rejected. The student continued to research schools all fall and found another school, one that actually might have been a better fit for their interests and plans. The student applied Early Decision II to this new school and was admitted.

- One student applied Early Decision to a school that felt like the best fit for their planned career combining engineering and entrepreneurship. They were rejected. They applied Early Decision II to a second-choice school that also felt like a great fit for this planned future. They were also rejected. Then, the student was admitted to a program within a large public university, one that awards two B.S. degrees (one in engineering, one in business) – a program even more selective than both the ED/ED II schools.

The stories could go on. The theme is simply that the process unfolds in its own way, on its own path. As students (especially rising seniors) approach the college process and begin their applications, it is so important that they keep this fact in mind: there is not only one path (or one school). Thirty years ago, I applied to college intending to major in Biology and head from there to medical school. Instead, I wound up studying philosophy (a subject I had never even heard of before my sophomore year in college) and going into education – a path I could never have conceived at 18.

It always works out – it just doesn’t always work out how you think it’s going to right now.

Empathy: Considering another’s perspective in a college application

In preparing their applications to college, high school students are encouraged to be authentic, engaged, passionate, and committed. These are indeed great aspirations, and, hopefully, kids get the message that being true and honest with themselves and putting together a good college application should not be at odds with each other.

One quality usually missing from this list of exhortations, though, might be the most important one: be empathetic. Empathy is a powerful idea whose definition often depends on context. For some, empathy is the same as sympathy, the state of caring for others and “feeling their pain.” It is an emotional response to a shared humanity. “I work in a food pantry for the poor because I feel bad for those who feel hunger; I teach kids how to play basketball because I know how much joy I get from it.” We believe such compassion to be a powerful part of children’s sociality and work to cultivate it. And when colleges ask applicants to write about how they help make the world a better place, it is this kind of empathy that students lay claim to and that admission officers wade through.

In urging students to feel sympathy for those with less privilege than they have, though, we might want to encourage them to do more than feel another’s pain. We also want to suggest a shift in perspective in which they go beyond describing their response towards imagining and interrogating how the other side in this equation feels. Social psychologists call this “perspective taking,” and define it as “the ability to understand how a situation appears to another person and how that person is reacting cognitively and emotionally to the situation.”

Why does this matter to how students present themselves in their college applications? In reading about or listening to how students describe their community service, I am always struck by how they see it as a one-way street: they feel bad for someone who might not have what they do and tell us what they have done to alleviate that need. They rarely seem to realize that there is also another side in this philanthropic equation. The result is variations on the so-called “poor but happy villagers” community service experience that has become so frustrating – and even toxic – to admission officers. They read countless essays about suburban kids teaching, contributing to, and “giving voice” to those who are less privileged. These essays are filled with good intentions but lack even a rudimentary understanding of the inequality and lack of reciprocity in such philanthropic exchanges: the less privileged are merely there to be acted on, to be helped and, hopefully, to be grateful for the assistance.

Don’t misunderstand me. I think such service work can be hugely enriching to a student and can reflect a well-honed sense of social obligation, which I applaud. But we might want to open a conversation with young adults – as parents and as counselors – about what and who is on the other side of that helping hand; to add to their emotional sympathy for the less privileged some of the awareness that comes from a more rational empathy.

Shifting perspective and seeing an exchange from the viewpoint of another, also offers students useful insights about other parts of the application process and, indeed, of life. When students present themselves in essays and interviews, it is often clear that they have not given much thought to who their audience is. It is a one-way conversation: they ascribe to themselves the qualities they feel colleges value (I am determined, helpful, diligent, resilient, keen to help others). It does not occur to them that what they’re trying to say may not be what the other side is hearing! They reference extensive foreign travel, for example, sure that the admission reader will appreciate their global citizenship, when, in fact, the reader hears a blithe catalog of great privilege. And when they describe tutoring an underprivileged fellow student, they rarely consider that admission officers might have been such low-income students themselves — and could find their tone patronizing.

As educational counselors we work in the hope that whatever kids learn from applying to college – about choices and consequences, about good writing – they will bring to bear on other parts of their young lives too. In this, there are few skills more valuable to them than moving from seeing the world strictly through their own eyes, to understanding that in their every interaction with another, there is another viewpoint present too.

How Heavy Is Your Backpack?

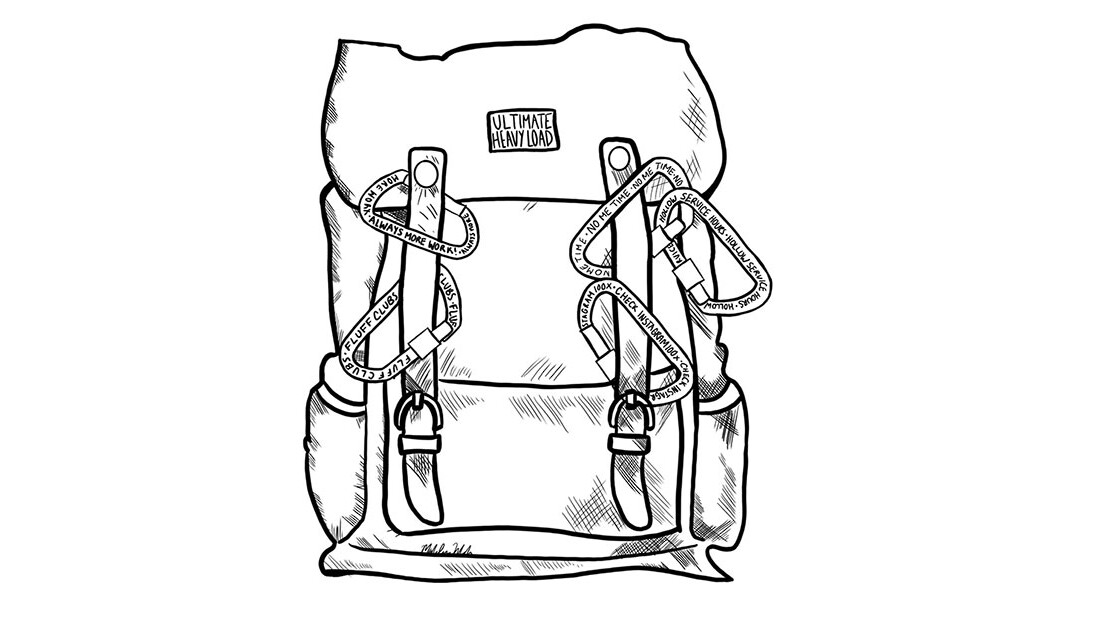

While I was walking through the snow (yes … we still get snow in March in Rhode Island) with one of my best friends a few weeks ago, she began telling me about a coaching framework she’s been working on—centered around a backpack. My friend Brountas (I call her by her last name … something that stuck during our college years together) owns an executive coaching business (https://www.linkedin.com/in/jen-brountas-16b731/). She uses the backpack analogy as a way to help her clients prioritize the things occupying their headspace. A backpack is a useful tool, but it has a limited capacity and a tendency to collect stuff that weighs you down. I couldn’t help but think that her framework and analogy could benefit my students as they transition into a post-pandemic world.

Brountas described her backpack idea as a way to talk about what feels awful and what feels good in our lives, and the consequences of letting the best parts of ourselves get lost in the load. I think a lot of my students would agree that the weight of junior and senior year of high school can “feel awful and overwhelming ” just like the weight of a too-heavy backpack. Everything about these later years of high school feels important … there is so much pressure to have just as heavy a backpack as everyone else, especially when thinking ahead to college. In fact, students often tend to “clip on” more responsibilities, like carabiners that create more weight on their shoulders.

“Think about what you miss and don’t miss” is a phrase I’ve heard many times over the course of the last year. I think most of us can quickly rattle off a few things we’ve missed throughout the pandemic and others we would happily toss out of our bags. It’s fun taking the time to reflect, but it’s much harder to actually leave some of your old life behind—to physically remove the weight or change the way you engage with the items that gnaw at your side. This spring, don’t just think about what’s next; instead, take action and make the leap forward to make your high school years the best they can be. A “big” bag full of all the right “things” doesn’t need to be heavy.

Stop & Unpack:

What “Rona” (as my students like to call the virus) did was force you to stop. It forced you to put aside your heavy load for a while. As Brountas says, “Feel the release. Step away from the bag and be conscious of what’s going on so that you can have a fresh perspective.” Before you sling the heavy bag back on your shoulders, I encourage you to unpack each item and sift out the “trash.” Is sitting on the bench at your team’s games getting you down? Maybe let that go and pick up something that makes you feel lighter and better represents the person you’re becoming.

Sort:

Sort the commitments in your life into categories: activities, clubs, the classes you’ve signed up for, jobs, internships, projects, time for sleep, time with friends and family, etc. What means the most to you? What would you like to leave behind? This act of reprioritizing isn’t something you should be ashamed of, it’s something you’ll have to do for the rest of your life. You’re just setting new goals!

Repack:

What do you want to take with you from the pandemic? Did you learn new skills? Strengthen your work ethic and confidence? Include these intangibles with your other priorities and make sure you have enough space — the type of space you enjoyed in your life as your heavy commitments shut down this year.

Try It On:

How does it feel? Is it still heavy in one area? Uncomfortably rubbing your side? If so, be aware of the irritating item in there that might need some reshifting. Maybe you just need to look at it differently? Perhaps a slight adjustment, like taking on a different role, forming a study group, or asking friends to join you in an activity can help make it feel more comfortable in your bag.

As schools go back to in-person learning, let’s talk through your re-entry and what’s most important — so that you don’t tip over from too heavy a bag. I believe a strong college application is closely tied to the joy and personal growth that comes from making good choices, and as Brountas says, “Monitor your backpack’s framework: it should be powerful and effective but not overwhelming.” An ideal weight, without filling your bag to the brim, allows you to walk with confidence and more intentionality as you move through your days and put time into what matters most to you.