Where are they going 2025?

As graduation season approaches, we’re celebrating the incredible journeys of the students we’ve had the privilege to mentor this year. The image below shows a glimpse of the colleges and universities our Class of 2025 students will be attending next fall, from flagship public schools to highly selective universities and everything in between. Each one is a reflection of their hard work, passions, and unique aspirations.

At College Goals, we believe there’s no single definition of success, no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to college. Every student’s journey is unique, and we’re here to help them find their best fit—whether that means shooting for the stars, discovering a new passion, or overcoming challenges along the way.

We’re so grateful to walk alongside families from all backgrounds through a process that can feel overwhelming at times—and to see each student find a place where they can thrive.

If you know a family looking for personalized, thoughtful college counseling, we’d love to connect. And feel free to share our website or inquiry form with anyone who might be starting this journey!

Words of Wisdom

At College Goals, we know that the best advice comes from students! Here is what our students from the Class of 2025 wanted to share with juniors who are just getting started:

“Honestly, I wish I had known how normal it is to feel completely overwhelmed during the college process. I was so stressed, constantly second-guessing myself, and there were moments where I truly didn’t think I could do it. It felt like everyone else had it all together, while I was just trying to survive the chaos. But the truth is, almost everyone feels that way—we just don’t always talk about it.”

“Looking back, I’d say the biggest advice I’d give to juniors is to start early, but don’t put too much pressure on making everything perfect from the beginning. Just getting your ideas down is a huge step. Also, don’t compare your process to anyone else’s — everyone has a different path, and that’s completely fine.

…And honestly, take breaks when you need them — burnout is real, and rest is just as important as productivity.”

“Mainly, stay organized and separate the essays you have for each school. The essays can seem daunting at first, but it’s very likely that you will want to reuse bits and pieces of other essays to help with the load. So make sure that they are all easy to find and won’t get mixed up.”

“I would emphasize having someone who knows you well and has some familiarity with the process suggest ideas. I also think the same goes for people offering feedback on your essays. You definitely don’t want too many cooks in the kitchen, and, aside from your counselor, I think one or maybe a second is largely enough to look them over…..”

“What I learned is that the college process isn’t just about getting in—it teaches you a lot about yourself. I spent so much time writing essays, trying to put my whole life into words, and in doing that, I started to understand who I am and what I care about.

I learned that it’s okay to change your mind, to revise (a lot), and that the best writing comes when you stop trying to impress people and just speak from the heart. And I learned how to manage my time better—deadlines come fast, and sometimes you just have to push through, even when it’s not perfect.

A tip I’d give? Start earlier than you think you need to. Even just brainstorming or making a rough list of schools helps take some pressure off later. You don’t have to do everything all at once—just take the first step.”

“It’s ok to completely rewrite essays if you have a better idea and … remember to consider a wide variety of schools.”

“I think my advice would be to do as much purposeful brainstorming as soon as possible. I think students should just jot ideas of genuine passions rather than trying to check any boxes at all.”

“If you’re feeling lost or unsure—you’re not alone. Keep going. You’re capable of more than you think.”

And finally, the Top Ten List:

1. Take time to relax over the summer, but your senior fall self will THANK you if you start early! I would say try to research colleges you want to apply to in June, work on your activities list and personal statement in July, and definitely start your supplemental essays in August. Make sure to visit some colleges if you have not already. Senior fall is an extremely busy time so you will be VERY thankful if you have a good chunk of your work out of the way.

2. Don’t let other people and their opinions dictate what colleges you apply or attend to in the end. There is no such thing as a bad college.

3. Practice writing your college essays by writing about everyday items and going into detail, or just getting some writing practice in general.

4. Have some safeties/likely colleges at least, because the college application process can be extremely unpredictable at times

5. Don’t be afraid to ask for feedback or help! Use your resources like your college counselors, and I also found it extremely helpful to have my friends peer review my essays as well

6. Try to make it…fun. Personally, I hated the process at first, but then I started to change my mentality and started enjoying the process of constant writing and reflecting.

7. Keep your entire senior year grades up because they can be important for things like waitlists

8. I would recommend doing most of the optional things in a school’s application, such as if a school has an optional video option or optional essays, because it will show demonstrated interest and that you care about the school.

9. Be kind to other people and mind your business–focus on your own college process, not where or how other people got in. There’s no point in college gossip and it distracts from what you should be doing

10. Read your emails because a lot of schools track demonstrated interest through the emails they sent you.

A Recommended Reading (and Listening) List

We here at College Goals wanted to share with you some of our favorite “go to” resources that are guaranteed to support your family through their college admissions journey. These endorsements are our own, not paid placements by any author or company.

If you want to listen to a podcast about college admission:

- “Inside the Yale Admissions Office” — This one got started during the pandemic shutdown, and they recorded a lot of great episodes about different aspects that go into selective college admissions. Episodes are topical (there’s one on letters of rec, one on activities, etc.), they are not too long, and there are no commercials. They have really slowed down in the posting since the pandemic ended, but they do release new episodes when there’s information to change (they did 3 excellent shows about Yale’s return to “test required” admissions). This show is also great for students who are not planning to apply to Yale! It is just straight answers about admissions, but with a focus on hyper-selective universities and their specific considerations.

- “The Truth About College Admission” — This brings together two of our very favorite communicators about college admissions (Rick Clark of Georgia Tech and Brennan Barnard who writes about admissions for Forbes among other places). In each episode, they interview someone in the field and reveal the “truth” behind the mythologizing that swirls around the admissions process. This is a great place to learn about topics like “institutional priorities” or athletic recruiting.

If you want to read a book about college admission:

- Who Gets In And Why by Jeffrey Selingo – Selingo, a long-time journalist writing about higher education, spent one year embedded in three different admissions offices (Emory University, Davidson College, and the University of Washington –Seattle). In his year, he observed the admissions “gatekeepers” as they made decisions. He also followed students (and parents), met with school counselors and others, and worked to understand and then dispel some of the misconceptions and mistruths that guide families as they consider admissions.

- The Truth About College Admission by Rick Clark and Brennan Barnard – This is the podcast in workbook form! This excellent guidebook sets up tasks and charts to support families through every aspect of the college process from building a list to constructing an application.

- The Price You Pay For College by Ron Lieber – Lieber, the NYTimes financial columnist, has long been an advocate for great clarity and transparency in the college financial aid process. This book is a must for any family looking to better understand how colleges set their costs and more importantly how families can navigate the complex financial aid landscape.

- I’m Going to College – Not You! edited by Jennifer Delahunty – For some lighter (and occasionally hilarious) reading, Delahunty, the former Dean of Admissions at Kenyon College, has assembled short essays by parents, students, college admissions officers, and college advisors that reflect on the student’s central role and growth in the admissions process. Two favorites are the piece co-written by Delahunty and her daughter about her own admissions journey, and Anna Quindlen’s reflections on swimming in the “deep pool” of her own growth as an undergraduate at Barnard College.

If you want to read a blog about college admission:

- Georgia Tech Admissions Blog – The GA Tech Admissions Blog is one of our favorites! There are so many posts that explain topics with incredible clarity. Some of our favorites include: Applying to College is not like the Movies!; How the Olympics Explain College Admission Part I and Part II – use the search feature to find topics of interest to you!

- UVA Dean J’s Notes from the Peabody – Dean J. at UVA, is an excellent explainer about confusing admissions topics (Should you send a resume? etc…) … plus, the dog is super cute!

And, finally, one amazing “go to” resource that includes a little bit of everything:

The College Essay Guy – Ethan Sawyer, aka “The College Essay Guy,” has made it a goal to share high-quality and thoughtful materials (free!) to support students through every aspect of the college application process. Not only does he have great resources to support your essay writing (including some amazing brainstorming YouTube videos), he has lists of great verbs to use in your Common App activities list, tricks and tips to tackle the supplemental essays at almost every school on your list, and so so much more!

To SAT? Or, to ACT? How do you pick?

The stress around standardized testing has not gone away despite the shifts that many schools have made toward test-optional admissions. In fact, for some students, the stress around standardized testing seems to have only increased as they consider how to maximize their scores to submit to schools that are test-optional (particularly when those schools seem to have a preference for students to submit high test scores). The specifics around whether “test-optional” really means OPTIONAL is a subject for another blog post. Today, let’s talk about the SAT and the ACT, how they are alike, how they diverge, and how you might be able to choose which test to take without going through the onerous challenge of sitting for both.

First, at the root, the SAT and the ACT really are very similar tests.

Both the SAT and the ACT focus on testing a student’s ability in the key areas of reading, writing, and math. They both ask students to solve problems, read passages, select among multiple-choice answers, and interpret information at a similar level of difficulty. Both the SAT and the ACT provide a standardized means of comparing students despite vastly different high school curriculums and experiences. Contrary to some outdated assumptions, neither the SAT nor the ACT has a “guess penalty” – which means that students should make a guess and answer every question on the test.

The really good news? Most students who take both tests receive a pretty similar score (percentile-wise) on each one.

Despite this, there are some key differences between the SAT and the ACT which might help students decide which test is the “right” test for them.

First, the ACT is a faster-paced test – students are required to answer more questions, per minute, on the ACT than they are on the SAT.

For example –

ACT math = 60 questions, 60 minutes (1 minute per question)

SAT math = 58 questions, 80 minutes (1:23 per question)

ACT English = 75 questions, 45 minutes (36 seconds per question)

SAT writing & language = 44 questions, 35 minutes (48 seconds per question)

ACT reading = 40 questions, 35 minutes (52 seconds per question)

SAT reading = 52 questions, 65 minutes (1:15 per question)

* Note: This applies to the paper-based SAT. The digital SAT (releasing in 2024) will be a shorter test.

SO – If you are a quick processor, someone who often finishes tests in school ahead of the allotted time, the ACT might be a better choice for them. If you prefer to work more slowly through information, or often find yourself using every minute of allotted time, the SAT might be a better fit.

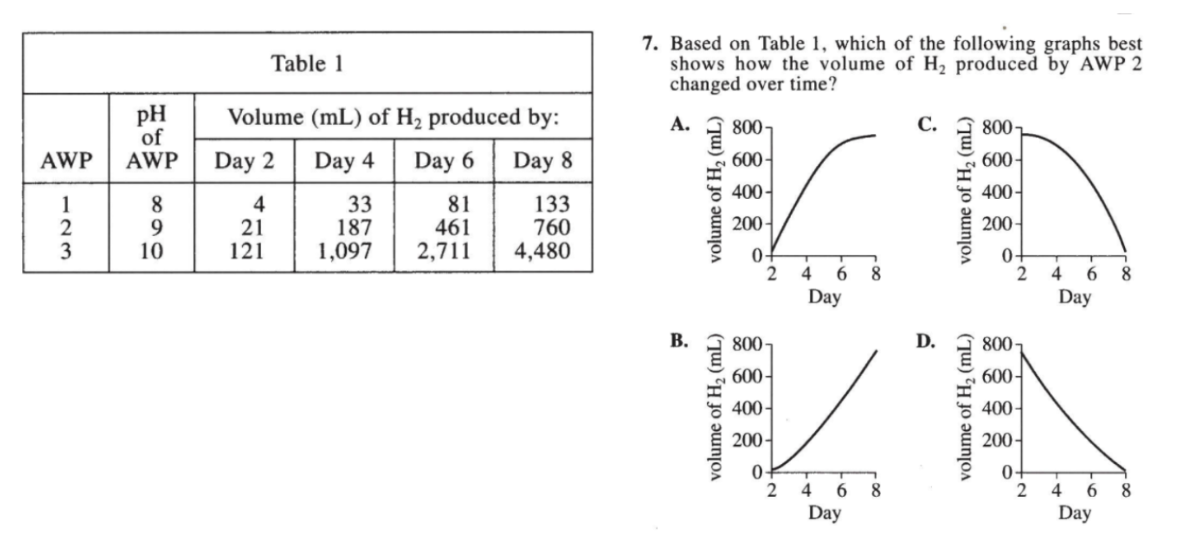

Second, the ACT has a science section. (The SAT does not!)

The science section of the ACT does not really test science concepts. It is really more about logic problems and graph reading. Take a look at this real ACT science question:

What do you think? Does the graph make your head spin? Or does this look like an easy question? (The answer is “B”.) If graph reading is not your thing, no worries, the SAT might be the test for you!

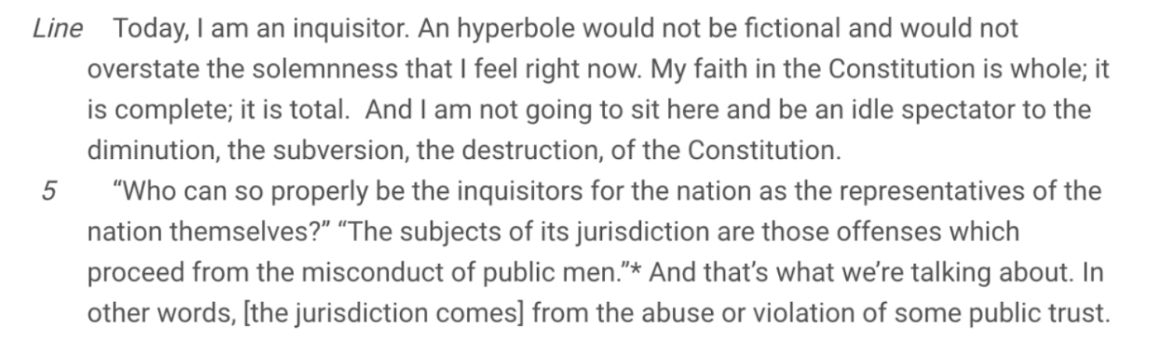

The SAT reading passages tend to be a bit longer, and tricker.

Do you love to read? How’s your vocabulary and ability to parse difficult passages? If you are a bookworm, or someone who loves getting lost in words, the SAT might be a more appealing test for you. Take a look at this real SAT reading passage:

What did you think? If this makes sense to you, maybe the SAT is a good fit test! If you felt lost here, perhaps consider the ACT.

Finally, the SAT has both a “calculator” and “no calculator” math section (only until 2024). For now, the SAT has one math section where students must rely on their mental math abilities. If mental math is not your thing, consider the ACT. However, when the SAT becomes all digital in 2024, the no calculator math section is going away.

The good news? Most of these differences between the tests will continue to be true, even after the SAT switches to digital testing in January 2024. Use some of these guiding questions to decide which test might be a better option for you! And no matter what you select, practice practice practice! There really is no better way to prepare than to be prepared!

It Always Works Out.....

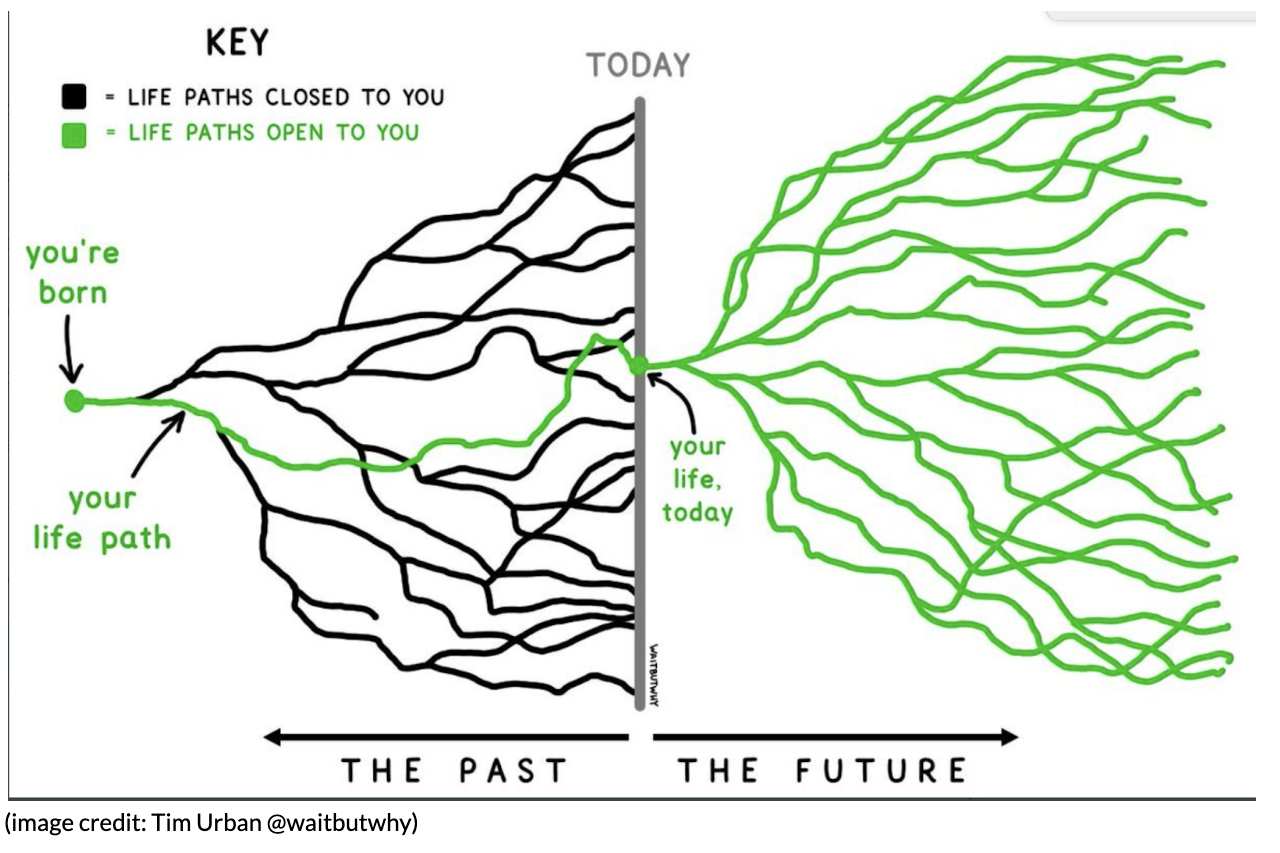

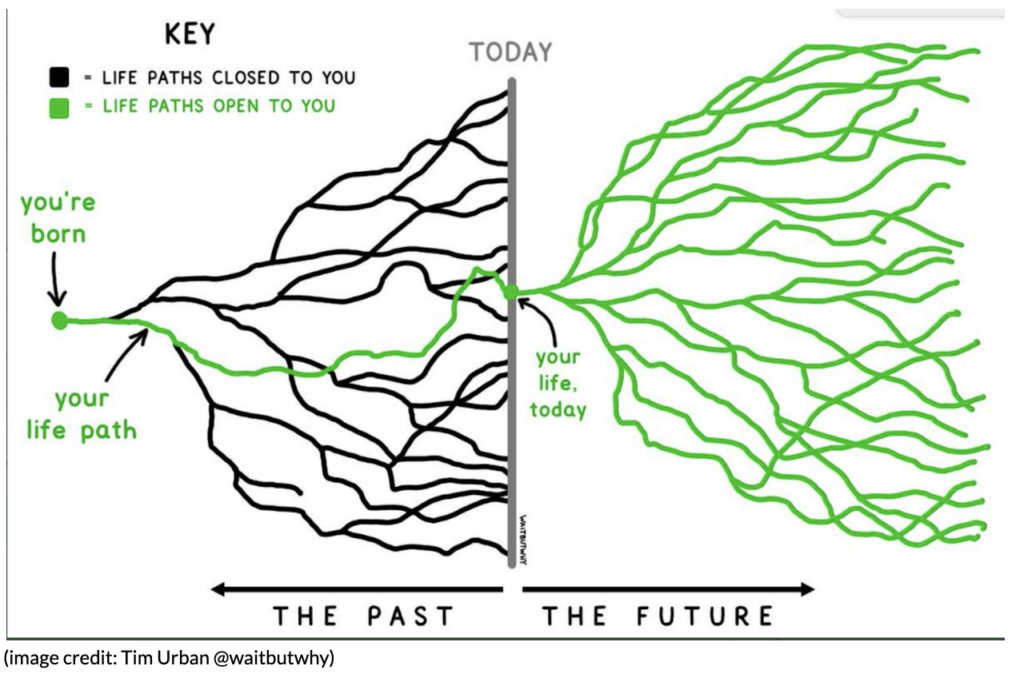

Take a look at this image. No matter who you are, or how old you are, your “today” is just the beginning of an infinite number of possibilities and branching paths.

Having worked as a college counselor for almost two decades, I can say for certain that many students look at their college decision as one of the most influential branches on the path that makes up their life up to that point. Often, when I sit down to meet with a student for the first time in 10th or 11th grade, they have a very specific vision of this path – what school they will attend, what they will study, and where their life will go from there.

Unfortunately, the reality of college admissions is that often these visions (this is the “dream school”; this is the “most perfect major”) do not play themselves out in the process. In the face of some schools receiving more than double the number of applications they received only a few years ago, it is more and more difficult to latch a set of hopes and dreams onto a single school.

But I truly believe that’s exactly as it should be. There should never be just one dream school, or one perfect program. The world is full of infinite paths and options – things students have never imagined or even conceived. Instead of seeing only a single path through the process, I challenge students to see themselves on the green line, and to begin to imagine the vast number of possibilities that lie in front of them.

Therefore, what I most often say to students (and families) throughout the college counseling process is this: “It always works out. It just doesn’t always work out how you think it will right now.”

Consider just a few stories from the Class of 2023:

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was deferred. The student applied to a wide selection of other schools at the regular decision deadline. Ultimately, the Early Decision school admitted the student in March. However, as the student looked at their options, there were others that felt like a better fit. Ultimately, the student enrolled at another school, one that wasn’t on the horizon as even a “high possible choice” in October.

- One student applied Early Decision to a “dream school” and was rejected. The student continued to research schools all fall and found another school, one that actually might have been a better fit for their interests and plans. The student applied Early Decision II to this new school and was admitted.

- One student applied Early Decision to a school that felt like the best fit for their planned career combining engineering and entrepreneurship. They were rejected. They applied Early Decision II to a second-choice school that also felt like a great fit for this planned future. They were also rejected. Then, the student was admitted to a program within a large public university, one that awards two B.S. degrees (one in engineering, one in business) – a program even more selective than both the ED/ED II schools.

The stories could go on. The theme is simply that the process unfolds in its own way, on its own path. As students (especially rising seniors) approach the college process and begin their applications, it is so important that they keep this fact in mind: there is not only one path (or one school). Thirty years ago, I applied to college intending to major in Biology and head from there to medical school. Instead, I wound up studying philosophy (a subject I had never even heard of before my sophomore year in college) and going into education – a path I could never have conceived at 18.

It always works out – it just doesn’t always work out how you think it’s going to right now.

Recommendation Letters and the College Application

As stressful as it is to write college application essays, at least the effort gives students a sense of control, of making a case for themselves by discussing what matters to them and what they believe makes them distinctive and wonderful. In contrast, letters of recommendation are written by teachers about students, who are expected to waive access to them.

By being proactive and thoughtful, though, students can still have significant input in these important pieces of the application. And they are indeed important. In the 2019 NACAC State of Admission report, most deans of admission put teacher recommendations in the same category of importance as application essays. But the number of required letters, and the guidance as to who should write them, will vary by college. Selective colleges will want to see one or two teacher letters in addition to the counselor letter, and they will usually ask that the letters come from junior or senior year teachers in core academic subjects (English, social science, math, science, and foreign language). Stanford, for example, suggests that you ask a sophomore teacher only if the course was an advanced one.

Some colleges also recommend that you opt for a balanced view of your performance by submitting both a STEM and a non-STEM letter. Indeed, a few schools – MIT, CalTech, Harvey Mudd and such – require such balance. But elsewhere, securing robust, personal letters should be your top priority. Of course, a breadth of intellectual interests may be a particular strength of yours, and you should try to reflect that quality in your choice of letters. But asking teachers who barely know you for a letter of recommendation, purely for the sake of such balance, seems risky.

Similarly, if your application reflects a particularly strong academic interest, whether in languages, engineering, or social justice, you can amplify the reader’s perception of your engagement with that field by your choice of letters. In fact, an application from a prospective engineer without a letter from a math or physics teacher might well raise questions about the depth of that student’s interest in the field.

Knowing that these letters really do matter to admission officers, what can you do to ensure that yours represent you in ways that will serve you best?

- Remember that at many colleges, applications pass through committees in school groups – everyone at one high school who applied to that college, one after another. If a teacher knows you only as one of many asking for a LOR, you might end up with the sort of note that will in turn reduce you to one in a crowd of applicants, all remarkably the same. So, choose a teacher with whom you have had opportunity to make some personal connection, perhaps by having conversations about shared interests.

- In choosing your letter writers, consider what a specific teacher might say about you (and perhaps has said already in a grade report or a parent conference). Can that teacher speak to your love of learning beyond working hard towards a good grade? Can the teacher address how your collaboration supports the learning of your classmates, beyond the fact that you are a pleasure to teach? Can the teacher come up with examples of your intellectual curiosity beyond mere diligence? If the answer is yes, then the teacher’s letter will help you seem distinctive in your role within a classroom community.

- Make good use of any opportunity to help shape the teacher’s perception of you, and help them represent you best. If the teacher asks you to complete a worksheet in advance, do so thoroughly and thoughtfully with an eye on the language and concepts that you wish them to use in describing you. Think of examples that earned you extra kudos from them for a particularly great job; or discuss sections of a course that challenged you to think a bit deeper.

Given your hard work on other aspects of your application, getting the best possible letters of recommendation deserves your attention. Most teachers work remarkably hard on these to do well by you – don’t forget to thank them! But an experienced admission officer can also easily spot the difference between a good LOR and an exceptional one. Aim for the latter!

AI and the Essay

It is now rare to open a newspaper or listen to a news program without some mention of AI. These discussions often have a slightly apocalyptic tone – the Terminators’ SkyNet lives! In essence, AI confronts us with a real transformation of the way we do things. And that is both hugely exciting, and scary.

Educators, too, are grappling with the implications of AI, particularly the way that ChatGPT (and alternatives such as Bard) upends assumptions about how we work. Evaluating students’ learning by asking them to write essays and exams, staples of secondary and tertiary education, now might become outdated. Asking students about the use of ChatGPT in their schools, most have told me they know others who use it for everything from basic information gathering to full-on essay writing. No one has acknowledged doing the latter themselves, and I think this reflects that students are as much at sea about this as their teachers.

When ChatGPT writes an essay, it produces content that is of higher quality than most high school students can deliver in terms of sophisticated word usage and clarity of argument. Its use might therefore be irresistible to students feeling the pressure of high expectations, busy lives, and an absence of clear guidance on the appropriateness of its use in particular fields of study and for different assignments.

As someone who loves technology but claims no education or insight into its development, I signed up for both OpenAI’s free version of ChatGPT and the more advanced GPT-4, to see what the fuss is about. Asking it to write commentaries on everything from the risks inherent in AI and obscure historical questions to why the San Jose Sharks played so badly this year (the answer turned out to be a litany of the obvious, from poor goaltending to “simply being outplayed”), it formulated answers in impeccable language, and certainly faster than I could have done.

But I think that ultimately there are three reasons why I would discourage students from using chatbots in their work with me:

- Having a chatbot do one’s work is arguably plagiarism: presenting someone else’s work as your own. As Stanford’s newly released policy on the use of any generative AI puts it, Absent a clear statement from a course instructor, use of or consultation with generative AI shall be treated analogously to assistance from another person. To quote ChatGPT directly, plagiarism is wrong because it violates academic integrity, undermines the value of original work, and is a form of dishonesty. (Colleges do recognize that there are academic spaces in which professors might well allow or even encourage students to use generative AI, including classes on the development of AI itself.)

- Secondly, for work in which we use writing to explain something or set out an argument, ChatGPT undermines learning itself. After all, learning lies not in presenting a final product for a grade, but the process that precedes it: creatively seeking out sources of information, critically weighing the validity of the information, and, after wrestling with competing ideas and conflicting evidence, using our command of language to construct an argument. Using a tool such as ChatGPT can sidestep that entire process.

- Finally, as an admission advisor, I don’t think ChatGPT will serve college applicants well in writing their essays. Admission officers look for many things in an essay, from good writing skills to critical thought, but also insight into how an individual student thinks, sees the world, empathizes with others, and might contribute to a campus community. Running one college admission question after another through ChatGPT, I was astonished at the speed and literacy with which it answered. But I was equally struck by how anodyne every answer felt. None of the responses had me in it.

I asked it, for example, to write a short essay on my identity as someone of South African descent, and ChatGPT quickly produced a well-written piece on how I have been shaped by the values of my family and culture and by the political struggles of my country. All quite true – of me and every other person who asks that question. Since it responds in broad strokes scraped from the experiences of others, it could not add anything about my unique experiences of how and where I grew up or adequately capture my distinctive voice. This is not ChatGPT failing. It is just the nature of generative AI and is what would make such an essay easy to read, but ultimately unsuccessful in its task.

In writing a college application essay, the task is not to produce the smoothest essay covering the broadest possible ground. Rather, it is to share something of what makes you uniquely and distinctively you. That can only be done by doing it yourself.

A tale of three college visits - which one fits you now?

Here in New England, it seems that winter still has a firm grasp on our weather, but soon, spring will arrive, and high school students and their families will start thinking about embarking on some college visits and campus tours. Your interest may have been piqued by hearing about admission decisions from the older students; you may notice flyers for college fairs posted at school; and you’ll probably be considering or even prepping for standardized tests. But springtime also brings the opportunity for college visits, in three different ways, at three different stages of your higher education journey:

- Just Browsing: Younger students may find that winter/spring holidays with the family can be the perfect time to pop over to a college campus. If your vacation travels bring you near a university, I suggest that you take a couple of hours to wander around. It could also be a great opportunity for your parents to enjoy a trip down memory lane if you find yourself close to their alma mater. Walk around, eat a meal in the dining hall, and pop into the Admissions Office to pick up materials. You may even find it possible to jump onto a campus tour. These visits can give you a good idea of the size, the ethos of the university, the culture, and the location. Do you want a college within walking distance of the town? Does the campus look well-maintained? How close is the airport? Public transportation? One question you’ll have is how you would get home during the holidays!

- Serious shopping: When spring arrives in earnest, high school juniors will be seriously considering college options, major studies, and lists of likely locations. Remember that you’ll be starting your applications during the summer after your junior year, because you’ll likely be applying to some colleges ‘early’ (November!). So serious college visits, campus tours, classroom visits, and admissions presentations are essential for your information gathering. Try to put together an itinerary that sensibly combines geographic locations – your parents will appreciate that. Always go online and make reservations for student-led tours and presentations. Find out who your admissions representative is and see if you can make an appointment for a one-on-one meeting with her/him. Really take your time now to explore the campus thoroughly and in-depth – check out residence halls, talk to students, examine the library, the computer labs, the science labs, and learn about support services both personal and academic.

- Ready to buy: It is true that many students apply to several colleges without ever having set foot on campus. But in spring of your senior year, usually by the end of March, you’ll have all your decisions, and it’s time to take advantage of special campus visits for admitted students. These will include overnight stays, classroom visits in your chosen academic unit, meetings with students and faculty, and a session with the financial aid office. The National College Decision Day is May 1, so all these visits must be completed by then. Parents frequently attend these Admitted Student Visits and are offered their own programs, but they typically won’t be staying on campus with their students. These are the visits that count – you are choosing your new ‘home away from home’!

This tale of three distinctly different types of college visits all ends up in the same place. The moral to be gleaned is that you need to start early, stay focused on your campus research, and have as many experiences under your belt before having to make your final life-changing decisions.

Choosing Your Courses for the Next Year

Soon, many sophomore and junior students must make choices about their courses for next year. We know the admission process at very selective colleges is based, above all, on your academic performance, and if your grades are not what the college wants to see, your chances of admission will be limited. But how do your curricular choices play out in that process?

Ideally, your college education should have both vertical depth in a single subject and horizontal breadth across many. Admission officers, especially at the most selective colleges, are trying to gauge whether your high school curriculum is equipping you, as a Harvard brochure on preparing for college described it, “with particular skills and information and … a broad perspective on the world and its possibilities.” In fact, most liberal arts colleges are not really admitting students to a particular major (there are exceptions, of course, mostly in pre-professional fields such as engineering and nursing). Thus, choices you make about your curriculum act as a mirror in which they can see your skill/aptitude for pursuing a particular academic interest, but also your curiosity and breadth of mind.

- Are you able to jump into challenging courses in your intended major and make good use of the opportunities on offer? Do you have the math training to take on engineering courses, for example? Do you have the analytical and writing skill to do well in a demanding philosophy course?

- Are you also able and curious to explore beyond your major? Are you flexible enough to see how those “other” ideas might even connect with your field and enrich it? This is as much a practical as a philosophical point. Knowledge is interconnected, and knowing something about statistics, for example, might be very useful to the prospective historian, while a pre-med’s perspective might be shaped by anthropological insights into different cultural assumptions about mind-body connections. In a rapidly changing world, you also don’t know what knowledge the future will require, or which bits of learning will start fading into obsolescence soon after graduation. Your career prospects, therefore, might depend on knowing how to learn, how to analyze critically, and how to communicate your great ideas, whether about a product you are developing or about a public policy you are promoting. You may well have developed some of these skills outside your major!

What does this mean for the courses you should choose in high school, especially if you intend to apply to selective colleges?

- Don’t specialize in high school – if you are mostly not being admitted to a major as a first year, then the fact that you avoided, for example, social science/humanities courses in high school because you intend to study data science, might be a red flag. Note that MIT and Harvey Mudd require applicants to have letters of recommendation from both a STEM teacher AND a humanities/social science one!

- Don’t choose courses because they might be easier, especially if you hope to apply to very selective colleges. Experienced admission officers know that a one-semester government class is likely not going to challenge you as much as AP US History, and that all IB math courses are not equally demanding. As Yale advises its applicants, “Pursue your intellectual interests, so long as it is not at the expense of your program’s overall rigor or your preparedness for college. Be honest with yourself when you are deciding between different courses. Are you choosing a particular course because you are truly excited about it and the challenge it presents, or are you also motivated by a desire to avoid a different academic subject?”

- Choose a course load that will show preparation in a broad academic core, because you will learn important skills and perspectives in each:

- History gives students a better understanding of how the past shapes the present and what is distinctive about our own moment. A rigorous economics course might do the same.

- English will help you write better in a global language and think more critically, while literature gives insight into other lives in different times and places.

- Foreign languages facilitate your access to a global world and to cultures that are not your own. Whether you want to be a businessperson or a physicist, being able to communicate with others and imagine different ways of being and thinking is essential.

- Mathematics not only allows you to balance your checkbook, but also to grasp new scientific discoveries, figure out the economic implications of environmental change, and understand a government’s trade policies. In short, mathematics equips you for modern life.

- Science, in a time when political freedom and environmental health are threatened by false facts and viral conspiracy theories, allows you to analyze scientific concepts and understand their consequences, and think creatively about technology.

- Finally, choose the right rigor for you. Students often ponder whether colleges care most about grades or about rigor. The stock answer is, of course, both. And if you aspire to ultra-selective colleges, this is good advice and a healthy reality check about your chances of admission. But it might not be the most useful advice for every student. NACAC, the national admission organization, counsels you to, “take the most challenging courses that are available and appropriate for you.” So, choose the toughest courses in which, with hard work, you can succeed, and then commit yourself to get as much from them as you can.

The 2022 admission season: what juniors might learn from it

With colleges having announced their 2022 admission decisions, I yet again feel like a recording stuck in a loop as I reiterate to my students that admission at the more selective colleges has become even more challenging. Even so, this year does feel different to me somehow. Perhaps it is the fact that I have seen more amazingly accomplished students who did not get into their dream schools – or indeed even into the ones they deemed target schools – than ever before, that makes the college admission process feel increasingly untenable.

While we wait for waitlists to settle down in coming months, though, a few themes have emerged.

- The University of California’s decisions have left counselors scratching their heads as top academic in-state performers found themselves denied or waitlisted by virtually every UC campus. An article in SF Gate that tracked the UC admit rates over the last 25 years, points out that in 1997 UCLA admitted 36%, UCB 31%, and UCSB, UCI and UCD all around 70%. Today those same schools range from 14% at UCLA and 17% at Berkeley, to 30% at UCI, 37% at UCSB and 46% at UCD. In all cases, Colleges of Engineering admit rates are far below that of each University as a whole.

- Knowing that, in a test-optional world, more kids feel free to apply to more selective colleges, schools are trying to figure what all the uncertainty and turmoil means for their yield, the number of students who will accept their offers. No one wants unfilled dorm beds or overfull classrooms. To help manage that uncertainty, many colleges are filling even a bigger portion of their first-year class with committed Early Decision applicants. The list of colleges that accept more than 50% of their incoming class in Early Decision – Bates, Bowdoin, Claremont, Colby, Haverford, NYU, Northwestern, and many others – is growing. Colleges also waitlist large numbers of applicants, and this year many seniors have found themselves waitlisted even at colleges where they had applied to an early program months earlier.

- Applicants to certain majors seem to have done especially poorly this year, especially in Computer Science, Data Science, Engineering, business and even some life sciences. Presumably this reflects both the huge numbers of applicants attracted to (or pushed towards) fields that seem to promise steady jobs and financial success, as well as the struggles of colleges to meet that surging demand with adequate research and faculty resources (in the five years after 2013/14, for example, the number of CS degrees conferred nationally increased by 60%).

What lessons might current juniors take from all of this?

- Take a healthy reality check from the admit rates. Remember that colleges with single digit admit rates have applicant pools full of strong and accomplished students (far more than they can admit) and the fact that you are one of them means you will be seriously considered. But at the end of the day those schools will admit students based on their limited space and institutional needs. Your college list must reflect the possibility that it might not be you.

- Build your college list on a thoughtful foundation of probable and possible colleges, knowing that a so-called safety is not simply a school to which you will likely be admitted but also one where you will still thrive. The litmus test of admission – if this is the only school to which you were admitted, will you attend – is more important than ever, and many high-performing students found themselves confronted with exactly that outcome.

- Think of your college list less as a series of set categories – probable/safety, possible/target, reach/ultra-reach – than as a dynamic process in which probability shifts according to application timing. Is a college still a target if you apply in Regular Decision, or does it fill so much of its class in Early that the admit rate is halved or even quartered for students applying in Regular Decision?

- Consider your academic narrative in which you explain what you want to study and why you want to do it at any specific college. Most colleges don’t assume you are fixing your major in place when you apply (there are a few exceptions) so discussing your intended major is mostly just an opportunity to show the college the critical depth and analytical skill you have to offer. BUT if the major on your application is in a field that seems overcrowded with applicants, or if it is clear from your limited curiosity that your intended field of study is simply a pathway to a steady job and good paycheck, it makes it harder for admission officers to appreciate what you have to offer academically. (See the recent guest posting on our blog about thinking beyond computer science as a major.)

- And finally, parents come to college admission with assumptions about the process derived from their own experiences and fueled with intense admiration for their children’s hard work and exceptional performances. But it is a different world from the one in which they applied to colleges and it requires new expectations. Thus, in 1990:

- Boston University had 12,400 applicants and admitted 45%. This year it received 80,800 applicants and admitted 14%.

- Northeastern University admitted 97% of its 10,600 applicants. This year, it received 91,000 applicants and admitted 7%.

- Stanford had just under 13,000 applicants and admitted about 22%; last year it received 55,470 applicants and admitted just under 4%.

- Columbia had under 6,000 applicants and admitted 32%; this year the school had over 60,000 applicants and admitted 4%.

- Cornell had about 20,000 applications and admitted about 30%; last year, over 67,000 applied and only 9% made the mark (Cornell is unfortunately one of the colleges that decided this year not to reveal its admission statistics).

- USC admitted a whopping 70% of about 10,000 applicants, bemoaning its declining enrollment; this year, it admitted 12% of the approximately 70,000 applicants.

For many seniors these days, the stress of college admissions feels less like the churning anticipation of preparing for a grand journey, and more like an anxious grind towards misplaced expectations in which much feels beyond one’s control. Perhaps it is only when they accept that their prosperity in life will depend far less on where they choose to attend than on the choices they make once they are on campus, that they will be able to reclaim the adventure.